The most common view is that there are four basic ‘models’ of health care in the developed countries, although in reality many countries have a mix of models.

1. The private insurance model

This approach has the least state involvement in direct funding or provision of health services. To get health insurance, you need to make regular payments to a health insurance company and in the USA – the only example in the developed world around 9% of the population are uninsured. Although the private health care market dominates, health services for senior citizens, for veterans and for the poor are publicly funded.

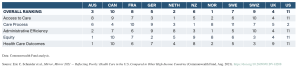

Medical debt influences Americans’ medical decisions – in a recent survey over a quarter of Americans said they have delayed doctor appointments and about 23% of respondents are paying off medical debt. An international comparison by the Commonwealth Fund concluded that the US healthcare system performs less well than other richer countries despite spending more per head than any other.

2. The social insurance (Bismarck) model,

Originating in 1880s Germany, with health care funded from workplaces, through compulsory payments by workers and employers in to 110 non-profit insurance funds.

This too has evolved, from the initial scheme begun by authoritarian Chancellor Bismarck, which was aimed at tying the most skilled, elite workers to the state rather than to powerful trade unions, towards the modern two tier system in which most people are covered by the basic scheme, but those on higher incomes (about 10% of population) are expected to pay in to a separate private insurance, provided by 41 insurance companies.

This model with variations has also been adopted by France, much of Central and Eastern Europe since 1989, South Korea and Japan.

Would European style social health insurance be the answer to the problems of the NHS?

3. The national health service (Beveridge) model,

First developed in New Zealand in 1938, which initially gave universal coverage, access to comprehensive services without charges, fully funded through general taxation, but most commonly linked with the British NHS established in 1948. Other countries that have adopted (and adapted) this model include the Scandinavian countries, Spain, and Italy.

Bismarck systems have always involved a split between “purchaser” (independent insurance funds) and public/private “providers” of health care. From 1980 onwards the Beveridge system in the UK has been increasingly “reformed” to create a similar division, and a competitive market (“commissioning”). In a number of countries public sector hospitals have been given varying degrees of ‘autonomy’ (trusts and Foundation trusts) and required to behave like businesses.

4. The Semashko (centralised, tightly controlled) model

Developed in the early Soviet Union by Bolshevik leader Nikolai Semashko, based on central, state funding, and free medical services to all. The key principles were government responsibility for health; a preventive approach, quality of care, and heavy dependence upon large hospitals, backed up by a network of polyclinics from 1928.

Strangely this system coexisted for years with Bismarck-style social insurance funds that were only abolished in 1937. The low costs of the model rested upon the institutionalised low pay and exploitation of staff: the lower status and pay of doctors led to a gender imbalance in which a majority of doctors were women. This model was exported to (imposed upon) Soviet-controlled Eastern Europe in the aftermath of World War 2.

And for the rest of the world

In addition to these basic models there are a number of hybrid health systems (Netherlands, Switzerland, Singapore) shaped by the politics of the country.

However, outside of the high-income countries many of the poorest countries that comprise most of the world’s population are heavily dependent upon donor funding for health care, and these have been pushed by the World Bank and IMF towards a FIFTH model, dubbed the ‘World Bank model’:

The “World Bank” model based on market style reforms was promoted in many parts of Africa, Asia, and Latin America from 1993, distinguished by maximum reliance on basic “primary care;” minimal public investment and hospital services; the widespread application of user charges (and insurance where possible); maximum involvement of private sector; and, often the involvement of the International Finance Corporation, the World Bank’s private sector arm.

Dear Reader,

If you like our content please support our campaigning journalism to protect health care for all.

Our goal is to inform people, hold our politicians to account and help to build change through evidence based ideas.

Everyone should have access to comprehensive healthcare, but our NHS needs support. You can help us to continue to counter bad policy, battle neglect of the NHS and correct dangerous mis-infomation.

Supporters of the NHS are crucial in sustaining our health service and with your help we will be able to engage more people in securing its future.

Please donate to help support our campaigning NHS research and journalism.

Comments are closed.