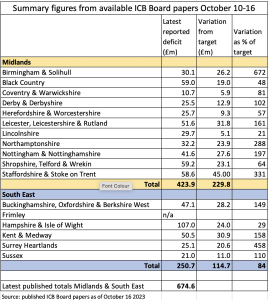

A new Lowdown round up of available Board papers from the 17 Integrated Care Boards (ICBs) in the Midlands and South East regions has revealed the extent to which systems are failing to achieve near impossible targets for savings to break even in 2023/24. These two regions’ combined deficits so far (mostly up to month 4 or 5) are £424 million (Midlands) and £251m (South East).

This is not far short of the £794m figure reported as the total Month 4 deficit across all 42 ICBs in England at October’s NHS England Board meeting.

All of the 16 ICBs which report reveal a worsening financial situation as they face substantial additional costs including inflation (not least in prescribing costs), continuing health care packages, mental health placements – and costs from continuing industrial action as the government drags out the dispute with junior doctors and accountants.

As a result all of the Integrated Care Systems (ICSs) in the two regions that have published financial figures are in deficit. However no figures are available from Frimley ICB, which has not met in proper session since June, and published no comparable financial report at that meeting. From what information is available it seems most unlikely that Frimley will prove an exception to the general picture of negative variances from plans.

The Midlands ICS deficits so far range from £10.7m (Coventry & Warwickshire) to £59.2m (Shropshire, Telford & Wrekin). As a percentage of the target for the relevant month the deficits vary from 21% higher (Lincolnshire) to a staggering 672% higher (Birmingham & Solihull).

South East ICS deficits (with no data from Frimley) range from £21m in Sussex to £107m in Hampshire and Isle of Wight, although the percentage variation from the target position ranges from 29% in Hampshire and Isle of Wight (which had initially submitted a deficit plan to NHS England) to 458% in Surrey Heartlands.

In many cases the ICB Boards are still clinging to their original projections for the end of the financial year, despite having slipped a long way behind in their projected savings and seen unavoidable cost pressures rising around them.

In many cases we may conclude that finance directors and Board members hope something might turn up that will enable them to avoid the cumbersome restrictions and bureaucracy imposed by NHS England on any ICBs that confess in advance that they expect to miss their targets.

It’s not only NHS budgets that are running short: Shropshire Telford and Wrekin ICB’s Finance Committee reported in September that a “deep dive” into the discharge of patients and the funding mechanisms with the Local Authorities had found that:

“all available recurrent funding has been deployed in the finance plan in support of the existing discharge services. The Committee discussed the fact that the current funding levels had been deemed insufficient for capacity required this year …”.

And there is a warning that “if an agreeable solution is not found between NHS and Local Authority partners this would have a severe impact on the Trust’s ability to discharge patients.” (p95)

Not all deficits are quite so large and troublesome: but no matter how optimistic some ICBs may try to be, the future is looking far from rosy. Last year (2022/23) Midlands ICBs ended up with combined deficits of £185m: this year their plans projected deficits totalling £173m – before many of the real additional and inflated costs were taken fully into account. (p182)

The Midlands region is no outlier: such deficits are far from unusual. Grant Thornton in an Auditors Annual Report on the state of Black Country ICS note the pressure on the whole of England’s NHS:

“Reducing expenditure and increasing productivity is now the priority for all NHS bodies. Cost savings or productivity improvements will necessitate wholesale redesign of services to deliver savings at a scale not seen for some years. Funding has increased from 2019 levels and yet productivity has not.” (p15)

However, as with last year, most if not all ICBs and Trusts are struggling to get through on the basis of one-off “non-recurrent” savings – which line up yet another year of misery next year as organisations carry through even more “underlying deficits” into an even tougher financial year.

Secretive discussions on cutbacks

Very few if any details have emerged on exactly what measures are being proposed and which services face “wholesale redesign” in efforts to balance the books. Keeping such information under wraps seems to be a deliberate policy.

We have noted in previous ICB surveys that all such measures in Cheshire and Merseyside and Lancashire and South Cumbria have been consigned to discussion in closed sessions of ICB Boards, preventing any public awareness or reaction to plans which may well impact on local accessibility and availability of services.

The Black Country ICB’s Auditor’s report also reveals that “Details of the ICB’s Operational Plan submissions for 2023/24 were presented to the Private … Board meeting in March and May 2023,” (p16) suggesting a similar secretive approach is likely wherever major efficiencies/cuts are being considered. The BCICB’s Operational Plan has still not been published more widely.

It’s bad enough for local people knowing that the priorities of the NHS bodies running local health services are focused on cash savings rather than improving and expanding services, but to have all of the plans formulated and adopted in secret session, preventing any prior knowledge or possibility for people affected to lobby on key issues, is even worse.

Even if there a few relatively harmless economies that can be made in some areas, by no means all savings, especially of large sums of money, can be achieved without impact on patient care, and the staff who deliver it. In Derby and Derbyshire ICS, for example, the effort to cut spending on agency staff has been translated into an agreement not to use agency staff to cover industrial action from Month 5: however the ICB Board has been warned:

“It is important to note that this approach, however, will create increased risks in relation to elective recovery and potentially patient safety.” (p159)

Kent and Medway ICB has established a System Sustainability and Transformation Group, attended by all the NHS Provider Chief Executives, and quite possibly by management consultants Carnall Farrar who have helped draw up an action plan – but not by trade union reps, patient groups or journalists. Its wide ranging terms of reference state its scope as:

- Review configuration of all locally provided NHS clinical services.

- Consider if any services location should be consolidated.

- Identify those services where short, medium- and longer-term moves may support improvements.

- Specific consideration of EKHUFT (East Kent University Hospital) in the absence of capital funding for a new hospital.

- Identify reconfiguration options.

- Financial consequences of options to deliver financial balance.

This group has apparently not only met but has also drawn up plans that are still not in the public domain:

“reviewed and agreed a draft case for change together with the common financial recovery model. The group will continue to work together on the ‘fragile’ services review, service models and work through the specialist commissioning delegation.” (pp25-6)

It is strange indeed that the same batch of Kent and Medway ICB papers that reveal the merest glimpse of these covert discussions, also includes an extremely lengthy consultation document and business case for a £4 million scheme to centralise and improve “place of safety” provision for mental health patients – on which there seems to be no controversy at all.

Campaigners, local journalists and news media, who are also excluded from such key decision making meetings on cutbacks and “savings” proposals, as well as health unions (whose members’ jobs and working conditions are potentially at risk in the drive for “productivity”) could usefully work together to demand an end to such secrecy.

Local campaigns should alert local people to the potential cutbacks, and press for full advance disclosure by every ICB of any and all proposals to cut spending by reducing services or staffing levels, and any cash-driven plans to reorganise services.

Use of private providers

It seems that a few more ICBs from this sample group of 17 are feeling obliged to make use of the private sector than appeared to be the case in previous similar Lowdown surveys. The driving factor is a combination of lack of sufficient NHS capacity to bring down waiting lists, and the latest “patient choice” policy. It also seems in some areas private high street opticians have been able to refer patients for regular tests and even cataract treatment and from private providers, which has led in some cases to overspending.

The National Patient Choice Programme, announced by Rishi Sunak in May, takes effect from October 31, and could create substantial additional instability, if not chaos. Northampton ICB Delivery and Performance Committee was told last month that the NPCP could mean as many as 3,000 patients could be “on the move,” raising questions about depleting budgets of local trusts and unplanned increases in spending on private providers. The scheme:

“would enable patients who had been waiting for 40 weeks or more, and met the require clinical and pathway criteria, to request to be referred to another Provider anywhere in the country who had a Commissioning Contract with NHS England or any Integrated Care Board for the required service.

“Patients could access the service via the Patient Initiated Digital Mutual Aid System (PIDMAS) and it was anticipated that Northamptonshire could see as many as 3000 patients on the move.

“… The National infrastructure to support this was not yet in place and accordingly the Committee reported limited assurance in terms of process and capacity.” (p167)

Herefordshire and Worcestershire ICB was already expanding the use of private providers. Borad members were told in its July meeting that “the plan is to utilise the independent sector further,” although nobody seemed quite certain about the details of the plan or its cost … or whether it is really a plan at all:

“A plan is in place that is currently around 120% of 2019/2020 activity delivery for the independent sector and, at the moment, part of this is funded through the baseline that was set for the 2023/2024 plans.

“… The initial assumption is that the independent sector are ahead of plan, which indicates that they are undertaking the work and bringing the backlog down as required, but there is now a need to work through and ensure that funding flows to cover that cost.

“Assurance was given that a plan has been built in at this stage.” (p15)

However there are other problems with private sector delivery in addition to the financial drain of NHS funds. Nottingham and Nottinghamshire ICB lists “independent sector activity above planned levels” as one of the reasons for (£1.2m) overspending at Nottingham University Hospital. (p275) But the ICB’s Quality report at the same meeting noted the rising number of patients coming in the other direction:

“an increase in the reporting of post operative infections relating to private provider procedures resulting in patients being admitted to NUHT. … There may be a gap in current reporting processes to capture these type of events as not all are infection related.” (p245)

Staffordshire and Stoke on Trent ICB’s October meeting heard of concerns with another private provider, Totally:

“The ICB have utilised contractual mechanisms with remedial action notices issued to Totally (NHS111 and GP Out of Hours) due to concerns around performance. The Remedial Actions Plans have not met satisfactory standards to provide assurance around delivery. The Urgent Care Portfolio are leading on managing the risks and impact across the system.” (p58)

No proper costings

One final factor seems common to almost all the ICB Board papers seen so far: while they are reluctant to spell out any details of proposed cash savings, they are equally evasive on the costs and staffing implications on the few positive plans that they do put forward.

Frimley ICB’s June meeting, for example sets out proposals to limit the “material underlying gap in resource availability” (an underlying deficit in excess of £151m) with measures to cut costs, including “Proacative Management Of High Risk Patients.”

This sounds like a perfectly reasonable idea, with plans to:

“Support up to 20,000 complex and frail patients and Care Home residents using remote technology via two centralised monitoring hubs (EBPC- NEHF, RBWM and Slough; BPC- Surrey Heath, Bracknell and Ascot). The roll out of remote monitoring to care homes will continue across 135 homes. On track to ensure 5,500 patients passed to digital health team by the end of 2023.” (p104)

But nowhere are the costs of the digital equipment and establishing the two hubs discussed, or the numbers of staff needed to make this a genuine service able to respond to increased health needs when they register on the digital screens.

Sussex ICS’s Winter Resilience planning includes “comprehensive discharge improvement plans” which have been “agreed between system partners”. It will, according to the report to September’s ICB meeting:

“reduce the number of NCTR [No Criteria To Remain] patients from 477 to 320 (a reduction of 157) and will release the equivalent number of beds, improving capacity, reducing the risk to patients of de-conditioning. This will enable patients to move to the most appropriate place of residence for their needs at the earliest opportunity.” (p8)

But the plans are effectively increasing the capacity of the system by expanding the availability (and therefore the number) of “appropriate places of residence” outside hospital, with the strong likelihood that the 157 vacated beds will swiftly fill once more after their long-staying occupants have been moved on.

In other words ‘resilience’ in the system comes at a cost of additional spending on facilities – and also needs additional staff in the community and primary care to ensure patients are supported rather than returning once more to hospital. All of this costs money: but no costings or staffing issues are discussed in the report.

Only much later on in the report is there an explicit reference to financial costs

“The resourcing of the System Coordination Centre (SCC) to allow the delivery of [NHS England’s] new SCC standards will need to be considered by the ICB following completion of the full impact assessment.” (p17)

After so many years of frozen budgets and real terms cuts in funding, it’s clear to all but ministers and NHS England that in many cases the ICBs with the biggest problems will need to be able to spend and invest more money before they can deliver genuine savings rather than outright cuts in services and staffing levels.

Full summary

Dear Reader,

If you like our content please support our campaigning journalism to protect health care for all.

Our goal is to inform people, hold our politicians to account and help to build change through evidence based ideas.

Everyone should have access to comprehensive healthcare, but our NHS needs support. You can help us to continue to counter bad policy, battle neglect of the NHS and correct dangerous mis-infomation.

Supporters of the NHS are crucial in sustaining our health service and with your help we will be able to engage more people in securing its future.

Please donate to help support our campaigning NHS research and journalism.