The publication of the manifestos of the three major parties has been followed by a barrage of useful information on the state of the NHS, from the Guardian and the Nuffield Trust, and a new Dashboard on GP services from the Health Foundation.

The common message is that after 14 years of under-funding and under-investment, the NHS is in such a poorly state that none of the main parties’ proposals are affordable within the limited additional funding they have proposed, and none of them tackles more than a small element of the problems that have grown since 2010.

Of parties with significant national following, only the Green Party on the left (uniquely calling for taxation of the wealthiest to fund their proposals) even suggest the much higher levels of spending that are needed to tackle chronic underfunding.

By contrast the ludicrous fantasy proposals of Reform on the far right rest on impossible assumptions.

The Green Party comes closest to acknowledging the scale of the current financial problems, when it argues the need for increases in both revenue and capital:

“we estimate that the NHS in England will require additional annual expenditure of £8bn in the first full year of the next Parliament, rising to £28bn in total by 2030. Additional capital spending of at least £20bn is needed over the next five years for hospital building and repair.”

By far the most damning critique of the three main parties comes from the Nuffield Trust’s redoubtable Sally Gainsbury, who warns of another five years of decline unless more money can be found:

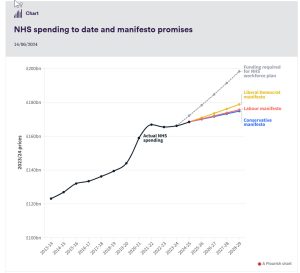

“… if any of the three parties’ pledges were implemented, the period 2022/23 to 2028/29 would see the tightest and most sustained NHS funding squeeze in recorded history (going back to 1979/80), resulting in annual real terms increases of just 0.4% under the Conservative pledges, 0.5% under the Labour pledges and 0.7% under the Liberal Democrat pledges.”

The squeeze would be “tighter even than the coalition government’s “austerity” period, which saw funding grow by just 1.4% real terms a year between 2010/11 and 2014/15.”

One crucial factor is that despite all the government claims, the varying promises of inadequate amounts follow on “three years in which NHS England’s spending has either been cut in real terms, or held close to flat.”

After last month taking stock of the real figures behind all the rhetoric of government spending plans since the massive NHS reorganisation took effect in 2013, Gainsbury’s analysis of the future prospects starts from the Office for Budget Responsibility’s base case for the next Parliament, and calculates additional spending promises above that.

The base case “assumes day-to-day spending across all government departments increases by a real terms 1% each year, while capital spending (on longer-term investments such as buildings and equipment) is frozen in cash terms.

“Applied to the DHSC [Department of Health and Social Care], that assumption results in real terms annual increases of 0.8%, and forms the funding baseline, on top of which we can compare each party’s pledged “extra”.

Gainsbury points out the proposed increases are so minimal that “without this assumption, the “extra” spending by 2028/29 pledged by each of the three largest parties would be insufficient to allow NHS spending to keep up with inflation.”

The amounts promised also all fall short of the projected cost of the NHS Workforce Plan, which all three parties have appeared to accept.

Gainsbury does not even discuss the huge issue of the likely freeze on capital spending, which makes a nonsense of Labour’s belatedly-included promise to implement the New Hospitals Programme set up in the aftermath of Boris Johnson’s cynical promise to build 40 new hospitals.

Labour’s surprising U-turn from insisting that all of the ongoing projects needed to be reviewed to ensure they offered value for money came at the same time as the revelation that delays in the Programme have cost Leeds teaching Hospitals up to £300 million, and that the standardised “Hospital 2.0” the Programme has been working on would also cost more to build.

But the freeze on capital spending under all parties’ proposals would also make it impossible to make serious inroads into the £11.6 billion backlog of maintenance of buildings and equipment – or to deal with the growing safety problems of 54 hospital buildings built with crumbling RAAC concrete.

Other Labour promises, such as to double the number of cancer scanners, would also eat into the frozen level of capital, while the promises of extra staff – 8,500 more mental health staff, thousands more GPs – and extra activity (some of it through the private sector) to reduce the waiting lists will need more revenue than the Manifesto proposals are promising.

No answers in private sector

The focus by both Labour and Conservatives on making increased use of private sector providers, supposedly to help reduce waiting lists, also implies an increased share of the limited funding (and increased numbers of vital staff) would be siphoned out of the NHS, rather than being available to strengthen services.

The policy has even been criticised by Justin Ash, chief executive of Spire Healthcare, the second largest chain of private hospitals, who has warned private hospitals cannot be expected to solve the crisis in waiting lists overnight.

“Nine of our hospitals are more than 80 per cent full. A lot of them are very busy. Solving a national problem like the pressure on the NHS requires a plan and it requires time. You can’t just flick a switch … You are talking years.”

Given the limited profitability of treating patients funded at the NHS tariff, Ash has argued that the ambition for Spire is no more than 30% of its caseload to be NHS patients. The most recent Annual Report showed Spire treated 196,000 NHS patients in 2023, up 8% from 2022: the NHS makes up 20% (one in five) Spire patients, and accounted for 25% of its income.

To increase the NHS share to 30% would, at most, take 100,000 more NHS patients a year – equivalent to just over one percent of the waiting list. It’s clearly not a quick fix for the backlog.

A new Nuffield Trust report also warns: “there are questions as to the extent to which spending a higher proportion of an already very tight budget on providers outside the NHS will lead to a further deterioration in the quality and sustainability of NHS-run services.”

One sector in which this negative impact is now worrying professional leaders is ophthalmology, where, as reported recently in the Guardian, the boom in high street opticians referring NHS patients directly to private clinics has led to nearly 60% of NHS cataract operations now being outsourced to private providers – more than double the 24% five years ago.

This is diverting scarce NHS funding away from treatment of more serious conditions that can lead to blindness.

While NHS spending on cataracts has doubled in five years, waiting times for some irreversible eye conditions also increased over the five years to April 2023. Last year the Association of Optometrists found more than 200 cases of people losing some or all of their vision because of treatment delays since 2019, and suspected hundreds more unreported cases.

But the switch of NHS resources from the full range of levels of need to prioritise the most simple, straightforward and profitable cases – and leave others to wait longer – is another inevitable consequence of increased use of a limited private sector, which has no interest in taking on any of the more complicated and risky operations.

Performance tracker

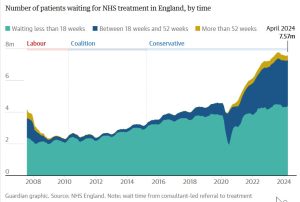

The accumulated problems that the incoming government will need to tackle from July 5 are set out in a series of useful graphs by the Nuffield Trust’s Performance Tracker, which shows the total waiting list creeping back up again after a fall which mainly rested on a change of counting to exclude some patients waiting for community health services.

It shows worrying data on cancer care. In April over a third (39%) of patients who had their first treatment for cancer following an urgent GP referral waited longer than two months – a long way from the target of only 15% of patients waiting this long, which has only been met once since April 2014.

The NHS is also still missing its target for 75% of patients to have their cancer diagnosed or ruled out within 28 days, with 70,302 patients waiting longer than this time in April, (11,796 more people compared to the previous month, when the target was met).

It also highlights that there were 42,555 trolley waits of over 12 hours in May 2024 – nearly 11,000 (35%) more than May 2023, and 100 times more than before the pandemic, when there were only 416 trolley waits over 12 hours in May 2019.

14 years summed up in charts

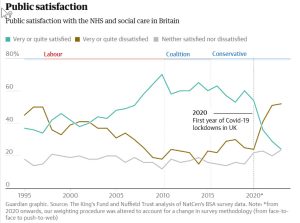

The Guardian, too, has presented useful charts and graphs that show how 14 years of Tory rule have changed Britain’s NHS. These cover some of the same ground as the Nuffield Trust performance tracker, but also include graphs showing falling public satisfaction with the NHS, the rapid growth of the bill for backlog maintenance, and the real terms erosion of NHS pay for nurses and doctors over 14 years.

General practice data

The Health Foundation’s handy new General Practice Data Dashboard, intended to “provide a broad picture of the state of general practice in the NHS, and how it is changing.”

It brings together useful information on numbers of appointments with GPs and other primary care staff, continuity of care, coordination with hospital services, patient experience and staffing.

It also covers funding, which is by far the weakest section because which appears to be presented only in spending, which appears to be rising in “real terms.” The calculation makes no correlation to growing numbers of patients in each practice, the increasing proportion of elderly, the decline and growing inequalities in public health, or the increasing range of tasks and services primary care has been required to take on. So this apparent generous increase in funding needs to be viewed warily. Let’s hope further updates present this information with more context.

Dear Reader,

If you like our content please support our campaigning journalism to protect health care for all.

Our goal is to inform people, hold our politicians to account and help to build change through evidence based ideas.

Everyone should have access to comprehensive healthcare, but our NHS needs support. You can help us to continue to counter bad policy, battle neglect of the NHS and correct dangerous mis-infomation.

Supporters of the NHS are crucial in sustaining our health service and with your help we will be able to engage more people in securing its future.

Please donate to help support our campaigning NHS research and journalism.

Comments are closed.