It has been hard to keep up with and evaluate the succession of announcements of new money for refurbishment and building projects that have emerged since the beginning of August.

The two major announcements were of £1.8 billion in capital to “upgrade outdated facilities and equipment” in early August, and the commitment at the end of September to provide another £2.7 billion to fund six new or refurbished hospital projects, with “seed funding” for another 34 postponed future projects – which will potentially cost another £10 billion or more – after 2025.

From the outset there has been scepticism on where the money is to come from. and whether or not more than half of the initial £1.8 billion for capital projects was new money at all: it was swiftly revealed that £1 billion of it was money already in Trust accounts, but which they were forbidden to spend by NHS England in a 20% cutback in July this year.

King’s Fund chief executive Richard Murray said it was “difficult to tell how generous the government is being, given a lack of clarity over how the schemes had been selected, and how the pledges fitted within the department’s overall financial settlement.”

The Office for Statistics Regulation has since stepped in to call for more accuracy in ministerial claims.

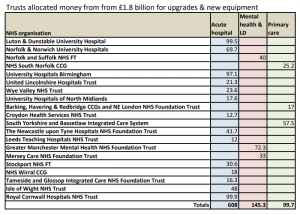

It was only some time after this first initial announcement that any details emerged on what schemes were to result from the extra money, and a list of 20 was unveiled, totalling £850m.

They are a mixed bag, in which 3 primary care projects for almost £100m, two mental health projects totalling £112m and a new unit for Learning Disabilities for £33m were outstripped by 14 projects in acute hospitals – an imbalance that has continued in the subsequent announcements of “new hospitals”.

The remaining £1 billion has now been released to be spent by trusts on the various projects that had been halted or cut back.

Capital-starved NHS

Some of this process of claim and counter-claim will have conveniently distracted from the harsh fact that, as the Labour Party has pointed out, in excess of £4 billion has effectively been cut or siphoned out of NHS capital budgets since 2014, much of it used to prop up trusts’ revenue budgets.

Indeed a hard-hitting campaign by NHS Providers, the body representing trusts, puts the figure even higher and calls for sustained increases capital funding for several years. They argue that:

“The NHS buildings and equipment budget has been relentlessly squeezed year after year. Over the last five years we’ve had to transfer nearly £5bn of that money to prop up day to day spending. As a result, the NHS now has a maintenance backlog of £6bn, £3bn of it safety critical. The NHS estate is crumbling and the new NHS long term plan can’t be delivered because we don’t have the modern equipment the NHS needs.”

A more detailed NHS Providers briefing document published at the end of August, arguing the case for restoring and increasing levels of capital funding, raises the shocking fact that:

“The NHS’ annual capital budget is now less than the NHS’ entire backlog maintenance bill (which is growing by 10% a year).”

It’s not surprising therefore that while welcoming the promise of any extra money for new buildings, NHS Providers was less than ecstatic about the over-hyped claims to be giving an immediate go-ahead for 40 hospitals, and keen to emphasise what was still a vital missing element:

“The NHS has been starved of capital since 2010. There’s a £6bn maintenance backlog, £3bn of it safety critical. It’s not just these six hospitals who have crumbling, outdated, infrastructure – community and mental health trusts, ambulance services and other hospitals across the country have equally pressing needs. We also need increased capital spending to support changes in the way care is delivered, including in IT and digital, to deliver the new NHS long term plan.”

Some of the projects appear to overlap with each other: a £99m scheme for a new children’s hospital in Truro among the 20 projects funded in August, for example, followed by inclusion of Cornwall on the list of trusts receiving “seed funding” for what was initially trumpeted as 40 new hospitals.

Then there was the 24 hours of uncertainty created by PM Johnson’s off the cuff statement on September 30 at Conservative Party conference that a new hospital in Canterbury was to be included on the list of new hospitals, triggering all kinds of responses from confused local MPs and campaigners – only to find that no new projects in Kent were included at all.

Nothing for mental health

Responses from the Health Foundation and NHS Providers to the funding announcements have flagged up ministers’ focus on headline-grabbing voter-friendly acute hospital projects, and the inadequate share of the new resources going to expand community health services, primary care and in particular mental health:

“None of the six hospital trusts given funding to develop a new hospital or the 21 trusts given seed funding in the government’s health infrastructure plan, and just three of the 20 hospital projects which received funding earlier in the summer, are mental health trusts.”

A new NHS Providers Framework for Community Mental Health points out the huge gap in provision that has opened up as a result of inadequate investment: “Core community services are a fundamental element of mental health provision. However, they have suffered from a lack of investment in recent years which has significantly impacted the quality of services and people’s access to them. Our report Mental health services: addressing the care deficit, found 85% of mental health trust leaders do not feel there are adequate mental health community services to meet local needs.”

NHS Providers’ analysis shows that the failure to prioritise investment in the mental health estate is having a real impact on patients: The number of reported patient safety incidents caused by infrastructure (staffing, facilities, environment) in 2018/19 was 19,088 compared to 17,693 in 2017/18.

“These incidents include unsafe environments with a risk to personal safety and inappropriate clinical environments.”

The number of infrastructure incidents, such as inappropriate disposal of clinical waste or wards that are too hot or too cold, in mental health trusts has increased by 28% from 2015/16 to 2018/19, compared to a 16% increase for incidents in all trusts. There were seven never events reported in mental health trusts in 2018 as a result of a shower/curtain rail failing to collapse and one as a result from a fall from a window.

Three lists of promises

So what has been agreed, where is the money going, and when, if at all, will the promised new projects begin to take shape?

There are three distinct lists of projects: the initial £1.8 billion (more than half of which has not been explicitly allocated); the list of six new hospitals given the “immediate” go-ahead; and the list of 21 trusts given a share of £100m of “seed funding” to work up projects to commence some time after 2025.

If these three lists are combined, the geographical distribution favours the East of England (11 projects) and the North West (10), in each case five of the projects allocated only “seed funding” and deferred to some time after 2025.

The South East is least favoured, being promised just 4, three of them post 2025 and one lump of £48m to redesign acute services on the Isle of Wight. The North East & Yorkshire region also has 4 projects, three from the £1.8 billion, and one of the more immediate projects – a development at Leeds General Infirmary.

Six of the seven projects announced for the South West are in the far future time frame beginning 2025.

The electioneering aspect of the proposals should not be forgotten either. Shadow Health secretary Jonathan Ashworth has also pointed out that eight of the 21 future projects cover Tory marginal seats, where even a tenuous promise of a new hospital might win a few extra votes: he named Hastings, Eastbourne, Winchester, Plymouth, Reading, Truro, Torbay, Barrow and Uxbridge.

Backlog bills

A closer look at the allocations from the £1.8 billion shows that three of the major acute hospital trusts stand to receive sums that are only a small fraction of their backlog maintenance bill: for Newcastle Hospitals this was £116m at the last count, Stockport needed £94m and United Hospitals of Lincolnshire £78m. So even after the belated “extra” money is received each of these trusts will still face hefty and unpayable bills for repairs just to bring their buildings up to standard.

Wye Valley NHS Trust has finally been allocated the money to replace the 1940s-built hutted wards that should have been demolished as soon as the PFI-funded hospital in Hereford opened in 2002.

The relatively small sums included in this list also underline the extent to which trust finances have been squeezed in recent years, making even relatively modest projects and what should be routine maintenance and replacement of equipment unaffordable without additional support.

No instant start

Of the six new hospitals that have been given the immediate go-ahead, none is ready to start work for some months to come, or even longer.

In South West London the long-running saga of the replacement of the crumbling St Helier Hospital in Carshalton that has dragged on for more than two decades is revived once again. Management of the Epsom & St Helier trust have decided the debate is about where to build a new £400 million “major acute” hospital.

Local people were once promised public money would be available to rebuild St Helier: but that promise was broken. Now they are promised Epsom and St Helier hospitals would both be retained as “district hospitals” – but a pale shadow of the current hospitals, with primarily outpatient and diagnostic services, an urgent treatment centre – and little more than half the 748 ‘core beds’ that were available in Epsom and St Helier earlier this year. An ‘Issues’ document last year stated clearly that “any potential solution with more than one major acute site … is eliminated”.

Local health chiefs now have to run a full public consultation in which they state where the new hospital should be, followed by development of a full business case. This story could run and run.

In North East London the announcement that the money is available will relaunch a similarly long wrangle over the funding and size of a new hospital to replace the ageing Whipps Cross Hospital, now subsumed into the morass of the Barts Health Trust. As with Epsom & St Helier the discussion has not yet even clarified where on the extensive Whipps Cross site the new building should be located.

After so many NHS capital assets have been sold off and the proceeds swallowed up covering trust deficits here will be some local concern at a “masterplan” suggesting a “new, taller, building on about one-fifth of the site” and alarm at the prospect of selling off the remainder of the estate “for much-needed new homes and community facilities.”

In Leeds, too, where the Teaching Hospitals Trust has been given the green light to proceed with building new hospitals for adults and children on the Leeds general Infirmary site, the Trust board is far from ready to begin work at once: “The Trust has a number of stages to complete before it can start building the new hospitals, but expects the build to take around three years once it is underway.” And as with Whipps Cross the project brings the prospect of land and buildings being sold off “to support the development of a new Innovation District for Leeds”. Some, like the Grade I listed Gilbert Scott Building “will be offered for sympathetic redevelopment to preserve their fantastic heritage for the city.”

In Watford, where West Hertfordshire Hospital Trust bosses have been “thrilled” by the funding to build a replacement, there is also an unresolved argument over the location of an acute hospital to serve the catchment area of almost 500,000 people, with non-Watford residents arguing strongly for a new build on a site that is not caught up in Watford’s congestion and proximity to the Premier League football ground.

Watford was selected as the main emergency hospital because at that time it was a very important 3-way marginal constituency: but it is the most inaccessible. It can take an hour or more by car from St Albans or Hemel Hempstead at 8am. By bus it is far worse – taking one and a half hours most times.

The problem will now have to be aired again with the development of a Business Case: the Trust has promised to share their proposals “as soon as possible”: the arguments will resume over how best to invest for future access to health care.

In Harlow, the announcement that the Princess Alexandra Hospital Trust is free to build the long-awaited and interminably-discussed new hospital has also left management “thrilled” but brought warnings that there will be some delay before anything actually happens. Chief Executive Lance McCarthy said: “We can now put into action our plans to speak with local people about their thoughts and suggestions on the new hospital to make sure that it meets their needs into the future.”

Princess Alexandra is a small hospital built in the 1960s for a much smaller caseload and which ended winter 2017/18 with bed occupancy above 99%: just 67% of A&E attenders treated or discharged within the target 4 hours.

There has been a debate over whether to patch up the existing building or replace it with a new £450m hospital on a “new” site, which may or may not be close to PAH. A Commons adjournment debate in June 2018 brought the statement from Health Minister Stephen Barclay that the STP bid for £500-£600 million to develop a new hospital and health campus on a greenfield site to replace the old hospital had been whittled down to £330m and referred back to NHS Improvement.

Local MP Robert Halfon pressed the urgency of investment: “A 2013 survey rated 56% of the hospital’s estate as unacceptable or below for its quality and physical condition. That was five years ago now and the situation is only deteriorating. With long-term under-investment, we are continuing to put the capability of the hospital to care for those in need at serious risk—just read the reports of raw sewage and rainwater flowing into the operating theatres.”

However it’s clear there will be a considerable delay between the new allocation of funds and the first bricks being laid in Harlow.

Likewise in Leicester, where the decision to give the go-ahead to the hospitals Trust to implement its reconfiguration of services is a sharp reminder of the unresolved debates over how services should be organised. Leicestershire and Rutland have just one acute hospitals trust, University Hospitals of Leicester (UHL), operating on three sites: for many years there have been plans to reduce this to two, with the loss of acute beds and services at Leicester General Hospital.

Now Chief Executive John Adler, professing himself “ecstatic” at the news that £450m is now available, has underlined this two-site strategy, arguing that the money would be enough for:

- A new Maternity Hospital and dedicated Children’s Hospital at the Royal Infirmary

- Two ‘super’ intensive care units with 100 beds in total, almost double the current number

- A major planned care Treatment Centre at the Glenfield Hospital

- Modernised wards, operating theatres and imaging facilities, and

- Additional car parking

A pre-consultation business case, reputed to be a staggering 1800 pages long has been kept carefully under wraps, apparently for fear local campaigners would begin to discredit its arguments before the carefully-spun official version could be established with local news media.

So the announcement that funding is in place for the reconfiguration heralds a fresh round or argument at local level. Campaigners will once insist that concentrating all the Trust’s emergency and most inpatient services on the already congested Leicester Royal Infirmary site makes little sense.

Before any new building can commence the Trust needs to brace itself for a full public consultation and construct a viable Business Case – which could also be open to challenge.

Impact on backlog

In total it seems that the six “new hospital” projects could eliminate up to £377m of the £6 billion backlog maintenance bill in England.

However the six trusts are already deep in the red, with combined loans to prop up their finances totalling over £700m, and planned deficits this year of £177m, so the terms on which the money is to be made available for the projects could make all the difference to their affordability.

The remaining 21 trusts that will receive less than £5m each in “seed funding” to begin to work up plans to begin in the mid 2020s are unlikely to see any major new building until at least 2027 – and some will have to find ways to manage some very significant backlog maintenance bills.

The biggest by far, and biggest in the NHS is Imperial Healthcare which needs £660m to tackle St Mary’s Hospital and its other sites, but will receive nothing for at least six years. Three other hospital trusts (Cambridge University, Hillingdon and Nottingham University) face backlog maintenance in excess of £100m.

Borrowing

While several of the 21 trusts whose needs have been put on the back burner are actually projecting a break-even or surpluses on revenue spending this year many are relying on rolling over loans from the Department of Health that have helped pretty up their balance sheets: these total more than £2.1 billion.

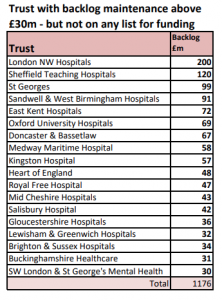

However at least these trusts have the distant hope of some relief, while many other trusts across the country face onerous backlog maintenance bills but do not appear on any of the lists of trusts singled out for extra cash. They have no prospect of being able to upgrade or replace their decrepit buildings.

Behind Johnson’s bravado and the obedient gratitude of trusts handed back part of the money they should have had over the past nine years is a stubborn and growing problem of backlog maintenance, continued neglect of investment in mental health, community and primary care services.

There is also a prospect of growing frustration in many areas that where people may have taken the announcements as good coin, and may respond angrily when they see no change in their local hospitals.

Worse, if Johnson succeeds in pushing through a no-deal Brexit and the warnings of the Institute of Fiscal Studies prove accurate, there would be serious doubts over the promises of future funding six years down the line.

Even with “substantial” government spending, the IFS expects the UK economy to flatline for two years, and forecasts government borrowing rising to £100bn.

The IFS warns that any rise in public spending in 2020 would likely be followed by “another bust” as the government would have to deal with “the consequences of a smaller economy and higher debt for funding public services. IFS boss Paul Johnson summed up:

“An economy that turns out smaller than expected can, in the long run, support less public spending than expected, not more.”

Dear Reader,

If you like our content please support our campaigning journalism to protect health care for all.

Our goal is to inform people, hold our politicians to account and help to build change through evidence based ideas.

Everyone should have access to comprehensive healthcare, but our NHS needs support. You can help us to continue to counter bad policy, battle neglect of the NHS and correct dangerous mis-infomation.

Supporters of the NHS are crucial in sustaining our health service and with your help we will be able to engage more people in securing its future.

Please donate to help support our campaigning NHS research and journalism.