In just over a year of publication, most issues of The Lowdown have carried reports on the continued inroads being made by the private sector into NHS budgets.

In May we attempted to draw a wider picture of the scale of private sector involvement, contrasting the real picture with exaggerated views that include occasional talk of “endgame,” and claims that NHS England’s Long Term Plan and other initiatives involving “Integrated Care Systems” – especially in the context of a possible post-Brexit trade deal with the US – are leading towards an American-style system, complete with charges for care and private insurance.

There were strong hints of this in Labour’s heavy emphasis during the election campaign on leaked documents on the US trade talks, and frequent statements that “Our NHS is not for sale.”

It’s not clear that this approach, which sadly underplayed much of the content of a very good section of Labour’s 2019 manifesto, was at all helpful, especially when it also appeared to ignore genuine and tangible local issues in many areas which should have given strong reasons for voters to fear a continuation of Conservative policy on the NHS.

It’s not clear that this approach, which sadly underplayed much of the content of a very good section of Labour’s 2019 manifesto, was at all helpful, especially when it also appeared to ignore genuine and tangible local issues in many areas which should have given strong reasons for voters to fear a continuation of Conservative policy on the NHS.

A closer look at the origins of privatisation in the NHS under the Thatcher government in the 1980s and its subsequent evolution shows that far from wanting to buy up and privatise the whole of the NHS, the private sector has always been happiest when it can win contracts to provide specific packages of services that will be paid for from the public purse.

Services are entrusted to the lowest-priced, least reliable contractor

Far from “selling off” these services, the NHS is “buying in” dubious quality services from private firms: far from flogging the NHS to “the highest bidder,” services are entrusted to the lowest-priced, least reliable contractor. And nothing is being sold: once the contract comes to an end, the contractors do not own any of the NHS. They can only continue if they win a further contract.

Even where clinical services have been privatised, the result is not a “sale” to create anything like an American-style system, but a private company, on contract, delivering services previously delivered by NHS staff, but which remain free at point of use and funded from taxation, often even sporting the NHS logo on buildings and uniforms. No wonder some people don’t recognise it as a problem.

It’s a far cry from the wholesale privatisation of telecoms, water, electricity, gas, and the railways, which were literally sold off to shareholders and corporations, but it is a real problem. Privatisation in health, in the political and economic context of Britain, almost 72 years after the establishment of the NHS, is the fragmentation and erosion of the public system, allowing the private sector to take a share of the public budget.

It’s a far cry from the wholesale privatisation of telecoms, water, electricity, gas, and the railways, which were literally sold off to shareholders and corporations, but it is a real problem. Privatisation in health, in the political and economic context of Britain, almost 72 years after the establishment of the NHS, is the fragmentation and erosion of the public system, allowing the private sector to take a share of the public budget.

It is pernicious and destructive, but it needs to be fought in a way that shows the wider public what the issues really are. So it’s useful to understand the way privatisation began to take hold, after 40 years of stability and apparent consensus on the NHS and other welfare services were brought to an abrupt end with the election of the Thatcher government in 1979.

From the outset they argued that bringing in private providers to the NHS was a way of cutting costs, and tried to downplay the extent to which this was at the expense of staff and standards of care.

Of course, the real agenda was what we now know as neoliberalism: minimising the scope of the public sector, holding down taxes on the rich and big business, and handing profitable contracts to their chiselling mates in the cleaning, catering and laundry industries.

Privatisation is a political move

As Hillingdon Health Emergency summed up in 1984: “The important thing to realise is that privatisation is not being done to save money or to direct more finances towards patient care. The evidence indicates that it costs money rather than saves it and standards fall drastically. Privatisation is a political move to line contractors’ pockets and destroy the power of organised labour.”

Indeed for Thatcher there was the added attraction that outsourcing low-paid but relatively well-organised hospital ancillary services undermined the trade union strength that had grown in the NHS during the 1970s and been a key factor in the prolonged series of strikes and protests over NHS pay in 1982.

The proposal to bring in compulsory competitive tendering to the NHS was first advocated by the Conservative Medical Society in a paper to the 1978 Tory conference, and after Thatcher won the 1979 election it began with a letter from the Department of Health and Social Security to all 192 district health authorities. It was largely ignored.

In 1982 a more strongly-worded draft circular was drawn up, but sidelined by the pay dispute. A heavily amended draft was reissued in February 1983, but it was not until after Thatcher’s second election victory in 1983 that the key circular HC(83)18 was issued calling for Competitive Tendering in the Provision of Domestic, Catering and Laundry Services.

This clearly reflected the impact of lobbyists from the industry: it states the government’s belief that the use of private contractors “under carefully drawn and properly controlled contracts” could “often prove the most cost-effective way of providing support services.” It presses health authorities to “test the cost-effectiveness of their … services by putting them out to tender (including in-house tenders).”

All District Health Authorities were given to the end of February 1984 to submit a timed programme for implementation, and told that they should not attempt to uphold any detailed requirements for staffing, or the length of time required for tasks.

Cheapness was the order of the day, not quality

Despite any other rhetoric, cheapness was the order of the day, not quality: “In no circumstances should a contractor not submitting the lowest tender be awarded the contract unless there are compelling reasons endorsed at district authority level …”

The Tory objective was clearly to ensure that private contractors secured as many contracts as possible, and this process was immediately branded as “privatisation” by the health unions of the day (NUPE, COHSE and NALGO, subsequently merged into UNISON, the GMBATU (now GMB) and ASTMS, now part of Unite) which began to step up their resistance.

To make matters worse, and enable even greater levels of exploitation of already low-paid workers, in the Autumn of 1982, and long before TUPE regulations protected the terms and conditions of staff transferred to another employer, the Tories had rescinded the Fair Wages Resolution of 1946, which had ensured that contracts let by government departments stipulated that contractors’ staff should receive pay and conditions in keeping with the general levels in the trade. The field was wide open to force through cuts in rates of pay and worse conditions along with loss of jobs and shorter hours.

Unions soon began to see the need to work with campaigners to develop publicity and information that could convey to a wider and largely uninformed public (who were mainly concerned about cuts in services) that privatisation was not just a threat to the jobs and living standards of health workers, but also a major threat to the safety and quality of health care.

Management resistance was strengthened by early contract failures

Some NHS managers were already reluctant to break up their established health care teams. Indeed ministers were forced to step in and force DHAs in Calderdale, South Cumbria, and Cornwall to hand over laundry contracts to private firms. Management resistance was strengthened by early contract failures – a quality check in Cheltenham revealed 84% of hospital pillowcases and 73% of sheets laundered by Sunlight to be below the required standard.

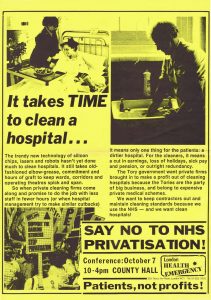

So campaigners and the unions began to collate evidence of the performance and the impact of private contractors – to encourage DHAs to steer clear of failing firms, and increase the chances of threatened staff fighting back. In publicity from London Health Emergency the cockroach symbol was used as a visual reminder of plunging hygiene in hospitals.

By April of 1984, at the same time as the great Miners’ Strike, the first major strike against privatisation had broken out at Barking Hospital in East London. As picketing continued and new disputes began around the country, the unions in London, together with GLC-backed campaigners London Health Emergency organised a 200-strong conference on Fighting NHS privatisation in County Hall in October 1984.

The message there was that the fight had to be waged not only against private contractors moving in but also against drastic cuts in terms and conditions to win “in-house” tenders that would also undermine the quality of services.

In June 1984 domestics at Hammersmith Hospital had walked out on what became a 3-month strike against an in-house tender which replicated all the worst aspects of private contractors, axing 40 jobs, cutting full-time staff from 123 to just 15, cutting the pay for most of those remaining on part-time by 50%, and halving the hours for cleaning the hospital. The strikers were finally sacked in September when the Special Health Authority voted to bring in private contractors Mediclean.

The relentless squeeze on standards also divided some of the Tories’ own supporters: in the autumn of 1984 Gardner Merchant, a catering subsidiary of Tory-donating Trust House Forte, pulled out of tendering for any of the NHS catering contracts to avoid reputational damage. “I have no desire to appear in the media accused of exploiting patients,” said MD Gary Hawkes, “Just imagine what it would do to us if we were running the catering where there was a food poisoning epidemic like there has just been in [Stanley Royds Hospital in] Wakefield.”

While Gardner Merchant stood down, up popped a new company, Spinneys, set up in 1983 to bid for NHS contracts, and immediately picking up contracts worth millions for catering, laundry, portering, security and gardening – without any experience in the NHS.

Long and growing list of contract failures

By the end of 1984 there was already a long and growing list of contract failures against some of the main players – including Crothalls (the firm that triggered the Barking Hospital strike by cutting hours of work and wages) who were fined in Croydon and Worthing and sacked in Maidstone for failing to meet standards and leaving nurses to do the cleaning; laundry firms Sunlight and Advance; Exclusive Health Care Services and Hospital Hygiene Services with failures in Leeds.

In some cases disputes against privatisation were victorious, and in other areas management themselves remained unconvinced of the merits of tendering. By October 1984 two thirds of domestic catering and laundry contracts awarded had gone to private companies, but by July 1985 the pattern had changed dramatically, with the percentage of contracts won by private firms reduced to 40%.

It soon became apparent that the high profits the private contract firms at first expected would not be forthcoming. A number of private contractors pulled out of tendering for NHS domestic service contracts including Sunlight, Reckitts, OCS and Blue Arrow. The finance director of Blue Arrow declared “there is nobody making any money out of the National Health Service”.

Moving the goalposts

With fewer contracts and lower profits than expected the private contractors began to lobby the government, urging ministers to “move the goalposts” to make it easier for private firms to win and retain ancillary contracts. On at least three occasions health authorities that attempted to award contracts in-house because they believed that the lowest tender by private contractor was unworkable were overruled by health ministers.

In March 1985 Bromley health authority had become so dissatisfied with the work done by Hospital Hygiene Services that they terminated their contract after six miserable months.

The option of dismissing unsatisfactory contractors had previously been argued by the contractors’ own trades confederation the Contract Cleaners and Maintenance Association (CCMA) as one of the advantages of the competitive tendering method. But as soon as it happened, Hospital Hygiene Services (whose directors included Tory MP Marcus Fox) immediately piled pressure on health minister Kenneth Clark, who within 24 hours authorised a telephone directive to all health authorities changing the rules in the contractors’ favour.

New rules made terminating contracts more difficult

Under the new instructions, no health authority could decide to throw out a contractor, no matter how bad their performance, without prior ministry approval. The delays this introduced into the process gave the company under threat the chance for a short period to throw extra resources into the contract to stave off the danger of dismissal, before reverting back to its unsatisfactory ways.

But even these changes were not enough for contractors. The beginning of 1986 brought news that Maidstone DHA had finally managed to break through the bureaucratic logjam and terminate its contract with Crothalls.

Once again out came a new set of directives from NHS management Board Chairman Victor Paige and yet further restrictions on the dismissal of incompetent contractors, discouraging even the imposition of penalty payments for unsatisfactory work.

Health authorities were now required to refer any proposed contract cancellation to both the Regional Health Authority and to the DHSS before kicking out a firm. They were prevented from asking contractors to specify performance rates of employees (opening the way for some of the more impossible workloads which had previously been the basis of artificially cheap private tenders.)

DHAs were also prevented from inquiring into the profit margins expected for particular contracts and from doing their own vetting of contract firms: they were told to rely instead on less discerning regional lists. Regions compiling approved lists were even told to avoid “intrusive” questions on the finance and competence of contract firms.

Plan for compulsory contracting out

The CCMA had drawn up an even more ambitious series of demands including the right for contractors to terminate contracts more easily, for health authorities rather than contractors to provide cleaning materials, and a reduction in the fines charged by health authorities when contractors failed to carry out their work. At the end of 1986 CCMA Secretary-General John Hall even argued that the government should abandon compulsory competitive tendering … and switch to a policy of compulsory contracting out!

However one of the reasons why contractors were having problems was that health authorities feared a loss of direct management control of the crucial ancillary services, and were less than impressed with the performance of the contractors already at work in the NHS. In this context is doubtful whether the Paige letter, making it much more difficult to ditch an incompetent contractor, made it easier for the firms concerned to win contracts.

By September 1986, the target date for completion of the tendering process, despite all of the efforts of ministers to force through private contracts the National Audit Office found that only 68% of the services by value had been put out to tender. Some health authorities, notably in Wales and Scotland had simply refused. The private sector had won just 18% of the 946 contracts that had been awarded. By February 1987 according to NUPE, 79% of contracts awarded had gone in-house with only 21% awarded to private contractors.

Plunging standards

But many in-house tenders were also under-cutting even the contractors, and further undermining the quality of patient care: contracting out – whether or not the private sector won the contract – was leading to a disastrous drop in hygiene standards that created ideal conditions for the spread of a new ‘superbug’ MRSA.

By the winter of 1987, as a massive new round of spending cuts pushed waiting list scandals onto the front pages of even staunch Tory newspapers, significant damage had already been done to the infrastructure of support services in what were increasingly overcrowded hospitals. A 1988 round-up of privatisation across London’s NHS compiled by London Health Emergency for the Association of London Authorities revealed the scale of the problem.

Many of these services in England have been repeatedly subjected to competitive tendering every few years since 1983, although the Welsh and Scottish governments since devolution have brought support services back in-house.

Even now some English hospital trusts have not learned the lessons of these failures. One example is as Luton & Dunstable University Hospital FT, which failed to secure adequate standards in a private contract in 2015, but is again showing that they have learned nothing from almost four decades of failure of competitive tendering, and offering a larger, less well-funded 10-year contract for cleaning and catering, while excluding any discussion of an in-house bid.

But with tendering in full flow, 1988 brought a new dimension to privatisation as the Thatcher government turned its attention to what we now call social care, and embraced a report proposing a massive privatisation of care for older patients that is still with us in England today.

Part 2 of this series will pick up the story from there.

Dear Reader,

If you like our content please support our campaigning journalism to protect health care for all.

Our goal is to inform people, hold our politicians to account and help to build change through evidence based ideas.

Everyone should have access to comprehensive healthcare, but our NHS needs support. You can help us to continue to counter bad policy, battle neglect of the NHS and correct dangerous mis-infomation.

Supporters of the NHS are crucial in sustaining our health service and with your help we will be able to engage more people in securing its future.

Please donate to help support our campaigning NHS research and journalism.