A new analysis shows that the NHS will be unable to get to grips with post-pandemic health challenges or make planned improvements without urgent steps on funding, staffing, and social care. A report by IPPR follows other evidence showing record waiting lists and a wave of new mental health distress. This article is a part of a series reviewing the key steps to build and protect the NHS.

____________________________________________________

Key points:

Staff burnout, long-term understaffing and NHS pay are pivotal issues.

The ambitions of the NHS Long term plan to improve care and raise survival rates cannot be met without increased funding and a solution for social care.

Lack of NHS capacity will make it more reliant on the private sector.

Technology can help, but many people lack digital skills causing major inequity in access to care.

There is a £9bn backlog in NHS hospital repairs and a lack of capital funding undermines community-based healthcare.

_________________________________________________________________

Funding

In 2020 the government gave the NHS £18 billion to pay for Covid-related spending plus an extra £3 billion one-off payment in the spending review in November 2020. But the budget in March 2021 gave no significant new money to the NHS.

Experts repeatedly told the government that the funding available for 2021/22 was insufficient to cope with the longer-term problems associated with the pandemic, in particular the backlog of elective surgery and the rise in mental health illness. There were warnings that services would have to be cut back.

The IPPR in its report – State of health and care: The NHS Long Term Plan after Covid-19 – published in mid-March 2021 estimates that the NHS needs over £12 billion in extra investment, including an additional £2.2 billion per year until 2025/26 to cope with the elective care backlog and rise in mental illness.

In late mid-March, Matt Hancock announced an additional £6.6 billion in one-off spending to deal with Covid-related spending over the next six months. There are however, issues with this figure according to Sally Gainsbury of the Nuffield Trust, who commented on Twitter that “it’s better than nothing” but it’s really a “bare minimum”.

The 10-year plan, published in early 2019, came with a funding settlement amounting to anadditional £20.5 billion for day-to-day NHS spending by 2023/24, which amounted to an annual rise of 3.4%. At the time the consensus of expert opinion, however, was that the NHS will need funding growth of around 5% a year over that same period in order to transform, modernise and develop services rather than just maintain services.

The pandemic changed everything; over the past few months extra funding has been provided by the government for pandemic-related costs.

Chief executive of NHS Confederation Danny Mortimer warned that “Should the Treasury budget discussions with the NHS fail to conclude this week, then we face the very real prospect of some services, particularly in the first few months of the new financial year, having to cut back.”

Staffing

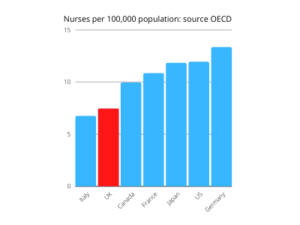

The content of the NHS People plan, which states that it seeks to change to a more compassionate and sustainable way of supporting staff, was enthusiastically received, but with a shortfall of 100,000 NHS staff before the pandemic, healthcare leaders have been frustrated at the lack of a credible plan to implement it; sufficient funding has not followed.

In July 2020 NHS England, NHS Improvement and Health Education England (HEE) published the final workforce plan for 2020/21, after sizeable delays and revisions from the interim version, and included some lessons from the pandemic.

However beneath the progressive thinking in the document the question of workforce shortages is unresolved, but now more urgent and a top priority for NHS leaders, and have fuelled wide skepticism about whether the NHS Long-term Plan, published in 2019 could achieve its major aims

. The Conservative Party manifesto promised to deliver 50,000 more nurses, 6,000 more GPs, and6,000 other primary care professionals. Nursing numbers rose by 6000 in 2020 and there are 7000 more in training than in previous years, but there is a long way to go. The number of GPs has not increased and many other areas are working with gaps in staffing.

In mental health services, one of the worst-hit by workforce shortages, a survey conducted by the British Medical Association (BMA) just before the pandemic began found 63% of mental health staff worked in a setting with rota gaps, and 69% of these said such gaps occurred either most or all of the time.

The pandemic has made workforce issues much worse. The IPPR reports that health and care leaders consider staff burnout as one of the greatest challenges of the pandemic. The annual NHS staff survey reported in the BMJ in March 2021 found that around a third of staff said that they were considering quitting their job, and a fifth indicated that they may leave the health service completely. There are also issues surrounding migrant healthcare workers, which the NHS relies on heavily, will seek other destinations as the UK tightens its migration rules.

The government has also ignored calls for a meaningful pay rise for staff – many of whom have endured pay cuts in real-terms over the past decade – instead suggesting a derisory 1%.

It is clear now that without sufficient funding, plus a meaningful pay rise for NHS staff – Unions have suggested 12.5-15% and the IPPR suggests 5% – then the People Plan 2020/21 will not avert a catastrophic loss of staff.

Saffron Cordery, NHS Providers deputy chief executive said: “We strongly support the commitment to prioritise staff health and wellbeing and to making the NHS a great place to work, but more investment is needed to make it a reality.”

COVID impact

An Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) report looking at how covid-19 was disrupting the aims of the NHS’ Long Term Plan (LTP), discovered that the number of cancers diagnosed while still highly curable has now fallen to 41 percent, against the plan’s target of 75 percent by 2028, resulting in 4,500 avoidable deaths.

New research from the Labour Party has also revealed shortcomings in cancer treatment during the pandemic. It showed that almost 330,000 cancer patients had missed the key NHS waiting time of two weeks for an urgent referral, while 13,000 waited over a month for treatment and 6,000 waited more than four weeks for surgery.

And this month a research study from Imperial College London found that cancer patients in the UK were more likely to die following a covid diagnosis during the first wave than patients across Europe, and that they were also less likely to have been receiving cancer treatment at the time of diagnosis because it had been paused during the pandemic.

The IPPR report also identified the highest cardiovascular mortality in a decade, with a further 12,000 avoidable heart attacks and strokes expected by 2025 if missed treatment ‘initiations’ are not made up for – this is against the LTP target of preventing 150,000 cases by 2029.

Following the publication of NHS England data for February, highlighting that nearly 400,000 patients were waiting more than a year to start treatment (the highest figure for 13 years), research unveiled by The Health Foundation earlier this month shows the number of patients who completed elective treatment last year was down by more than 4.5 million (ie around 25 per cent) compared to 2019 and could swell to 9.7 million,

The charity also revealed that patients who need to be admitted to hospital are now waiting longer than those who can be diagnosed and treated remotely, that access to elective treatment fell furthest in the most deprived areas, and that six million fewer people were referred into consultant-led elective care.

But the pandemic is hitting NHS staff as well as the patients they care for. In addition to the well-documented stresses of working on covid wards over the past year – last month the IPPR revealed that 100,000 nurses and 8,000 midwives were likely to leave the NHS because of those pressures – new figures from the Office for National Statistics show that at least 122,000 health service personnel are now suffering from long covid, putting an extra strain on a service that is already vastly understaffed.

And mental health charity Mind’s recent survey of emergency responder staff and volunteers found that 75 per cent of ambulance staff said their mental health had worsened since the pandemic began.

Technology

The NHS Long Term Plan, published in early 2019, envisioned the NHS eventually offering a ‘digital first’ option for most services, and this aspiration was quickly fast-tracked to meet the public health challenges of the pandemic last year, leading health secretary Matt Hancock to tell a meeting of the Royal College of Physicians last July, “From now on, all consultations should be tele-consultations unless there’s a compelling reason not to.”

Take up of these digital opportunities has been rapid, with GPs and hospital consultants now regularly conducting patient consultations over the phone or via Zoom, developments such as smartphone-enabled ‘wearable’ tech featuring in NHS England’s roll-out of its At Home programme, and the growing use of apps such as the Hancock-endorsed GP at Hand product from Babylon Digital Healthcare.

But, as The Lowdown noted earlier this year, data sharing and the dystopian prospect of NHS patient records being monetised is as much a feature of the ‘digital first’ era as patient safety in a public health emergency.

One element of last year’s fast-tracking was the suspension of section 251 of the National Health Service Act 2006, which then allowed NHS trusts, local authorities and others to process confidential patient information without consent for covid-19 public health, surveillance and research purposes.

Although there has been no suggestion that the suspension has benefited commercial interests in any way, tech-savvy patients will no doubt be aware that major players such as Google, Amazon, Microsoft and Palantir have been helping the NHS meet its data requirements for some time now.

And online access – or lack of it – remains a significant barrier to widespread take-up of digital tech for some. More than 10 per cent of people lack access to a decent broadband service, a similar number lack the skills or resources to access such a service, and others are excluded because of a mental or physical disability. NHS Digital backs this up, saying take up of its various digital health initiatives is constrained because 11,300,000 people lack the basic digital skills to use the internet effectively, and 4,800,000 never go online at all.

Buildings

The NHS ‘estate’ is in a poor condition, ill-prepared for the challenges of social distancing and remote consultations.

In 2019/20 – the latest figures available – the cost of clearing the hospital maintenance backlog alone was estimated at £9bn (up 40 percent on a year earlier) and much of that backlog related to risk issues dating back to the 1960s and now identified as ‘significant’, potentially impacting on patient safety.

The role of PFI consortiums is contributing to the problem. Last year the National Audit Office noted, “PFI providers have an incentive to limit expenditure on maintenance and rectification work in the final years of a contract.”

The situation in primary care (where barely 50 per cent of GP surgeries consider their premises fit for current needs) and social care (where it’s estimated that more than 80 per cent of care home stock is over 40 years old) is no better. Both sectors need major investment.

But given the scale of the problem the response from the Department of Health & Social Care has been underwhelming. The £600m in new investment unveiled by health secretary Matt Hancock last year, for example, barely scratches the surface when it comes to “building back better”.

And the government’s ‘aspirational’ plan to build 40 new hospitals appears to be just more of the same. The promised £3.7bn funding for them will struggle to meet the actual £20bn construction cost, and so the bulk of the money pledged is expected to go to just six sites.

The much-hyped Nightingale concept, introduced to bolster the NHS estate during the pandemic, has failed to add anything to the mix bar eye-watering expenditure. Earlier this month it was revealed that the Nightingale hospital in Bristol – which cost £16m to set up, and a further £1m a month to run – closed at the end of March, despite never having treated a single covid patient.

One group making a stand on the issue of inadequate buildings is the One Voice coalition, a campaign to improve maternity facilities. Its co-chair Gill Walton told Health Business magazine, “Many of the buildings used [for maternity services] are old and in need of repair. They are simply not fit for purpose.”

Privatisation

Hundreds of contracts for services/products related to the pandemic were given to private companies. Now firms see the huge pressure on the NHS as a prime opportunity to expand their share of the NHS budget.

In March 2020, the pandemic led the government to adopt emergency procedures for contracts, which meant that contracts were no longer put out to competition. Large contracts have been handed to companies like Serco, management consultants and private hospitals, with no competition or scrutiny. Over the following months numerous media reports appeared highlighting major problems with these contracts.

In November 2020, the National Audit Office (NAO) published two damming reports on the government’s buying and outsourcing procedures since March. The reports criticised the use of ‘VIP’ channels for companies that had connections with MPs, the Conservative party and its contacts, and also the massive amount of money wasted on buying PPE.

In February 2021, Operose Health Ltd, the UK arm of the large US healthcare insurance provider Centene Corporation, acquired AT Medics, which operated 49 GP surgeries across London, providing services to around 370,000 people, with 900 employees.

In the same month a leaked copy of the government’s White Paper included plans to scrap the much criticised competition rules, which allow commercial companies to bid for a vast array of NHS contracts and were a keystone of the Tory health reforms of 2012.

This change of heart about privatisation of the NHS, contrasts sharply with what has happened in the pandemic with contracts. However, this change may well have little impact on the NHS.

It is a positive that the NHS will no longer have to waste time and money on tendering out contracts, but the reality is that the private sector has already won £20bn in contracts throughout the competition era, according to figures from the NHS Support Federation, and there is no sign of these contracts being transferred back into the NHS. Prior to the pandemic, the NHS did not have the capacity to take these services back in-house, now with the backlog in elective care and rise in mental illness, the NHS will be forced to continue to seek help from private companies for some time to come, unless sufficient funding is provided to boost the NHS’ capacity.

– Future articles in this series will look at the NHS integration project and the forthcoming legislation.

Dear Reader,

If you like our content please support our campaigning journalism to protect health care for all.

Our goal is to inform people, hold our politicians to account and help to build change through evidence based ideas.

Everyone should have access to comprehensive healthcare, but our NHS needs support. You can help us to continue to counter bad policy, battle neglect of the NHS and correct dangerous mis-infomation.

Supporters of the NHS are crucial in sustaining our health service and with your help we will be able to engage more people in securing its future.

Please donate to help support our campaigning NHS research and journalism.