The phrase ‘incomplete pathways’ – NHS-speak for waiting lists – didn’t feature in the four-step roadmap offered up by the prime minister two months ago, but it represents a major roadblock on his ‘route back to a normal way of life’, one which will take years to clear.

So how bad is the situation?

Earlier this year the centre-right thinktank Reform warned that waiting lists for hospital treatment could more than double by April and soon hit ten million in England alone. It claimed that six million fewer patients were referred to treatment in 2020 than in 2019, and that cancellations of diagnostic testing and delayed treatment may lead to more than 1,660 extra deaths from lung cancer alone.

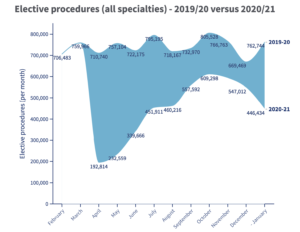

Year-on-year data for January and February, released this month by the British Medical Association (BMA), shows the extent of this rapidly growing problem:

– the number of patients waiting more than 12 months rose 185-fold, from 1,643 to 304,044, the worst performance against this target since it was set in 2008 (NHS England actually introduced a zero tolerance of waits of more than 52 weeks in 2013-14)

– there were three million fewer elective procedures and almost 21 million fewer outpatient attendances

– the elective treatment waiting list increased to 4.59 million, a likely under-representation of the total, due to a drop in referrals since March last year

– 66.2 per cent of patients were treated within 18 weeks, down from 83.5 per cent in January last year (the NHS England standard, introduced in 2012, is 92 per cent)

– just 139,378 patients were admitted to a bed for consultant-led treatment, down 54 per cent on the January 2020 figure of 304,888

– the NHS England target of treating 85 per cent of cancer patients within two months of an urgent GP referral was missed again (the target has not been met for more than five years)

Historic problems

In its latest report on waiting times, the King’s Fund thinktank – echoing information from an earlier NHS annual report – reinforces the idea that the problems experienced by the health service are historic, as well as being driven by the pandemic:

– the four-hour waiting time standard for A&E services hasn’t been met since July 2015 (but it was still a shock to hear a Royal College of Emergency Medicine spokesperson tell the BBC that the number of hours ambulances spent waiting to offload patients in some parts of England was “off the scale” in January this year)

– the 18-week waiting time standard for planned elective care hasn’t been met since February 2016

– by December there were more than 220,000 patients waiting more than a year for routine planned care, compared to only 1,500 people in December 2019

Looking in more detail, the online news site HSJ analysed provisional data from NHS England on various health sectors recently and found that ophthalmology patients had been particularly badly hit by the knock-on effects of the pandemic on surgical capacity. The number of patients waiting 52 weeks or longer for ophthalmology treatment (mostly for cataract surgery) had increased to more than 23,000 in December – up 57,580 per cent (just 40 patients) on the year before.

Waiting lists like these – and the impact they have on patient outcomes – have obviously been made worse by the pandemic, but their origins pre-date it by at least a decade, and their impact, following years of under-investment in the NHS, was clearly evident in the months leading up to the first lockdown.

In March 2019 the number of patients waiting to start planned, consultant-led hospital treatment was 4.23 million, up 10 per cent on the same period a year earlier.

Just before the 2019 general election the Health Foundation published a list of priorities for whichever party would end up in Number 10, and it chose to highlight that England then had: the highest proportion of people waiting more than four hours in A&E departments since 2004, the highest proportion of people waiting more than 18 weeks for non-urgent (but essential) hospital treatment since 2008, and the worst performance against waiting times targets since those targets were set. It also called for more staff and investment in the NHS and social care, to help reverse lengthening waiting lists.

And a few months later, just weeks before the first lockdown, the charity Brain Tumour Research shone a spotlight on NHS England statistics showing that 64 per cent of hospital trusts had missed cancer waiting times – with 2019 being the worst year since the targets were introduced – and that the number of those who had to wait longer than two weeks for a first appointment with a consultant after an urgent cancer referral from a GP increased by 30 per cent, up 50,000 from 2018.

Hole in the budget

Chancellor Rishi Sunak’s decision not to award the NHS any extra cash in last month’s budget to help it cope with the pandemic came as a shock to many, and has only been partially offset by health secretary Matt Hancock’s subsequent award of an additional £6.6bn a few days ago. This figure was considerably less than the £8bn sought by NHS England chief executive Sir Simon Stevens when he addressed MPs in early March, and may have little impact on waiting list pressures.

As the King’s Fund acknowledged last month, extra funding made available by the chancellor last year to procure extra capacity from the private sector may go some way to relieving waiting lists, but the scale of the backlog means that it will still “take several years before access standards are routinely met again”.

That’s an outlook shared by the Royal College of Ophthalmologist’s Melanie Hingorani – who told HSJ that clearing the ophthalmology treatment backlog could take more than two years, adding, “And maybe we [will] never catch up” – and also by one un-named acute trust boss quoted by the Guardian this month, who said, “I think [the backlog in cancer and heart disease surgery] will take many years. How long? Who knows?”

Similarly blunt assessments no doubt informed the call last July by the Royal College of Surgeons for a “plan for recovery” to address the “bomb” that had “already detonated” under surgical waiting lists. Sadly, eight months later, the government has yet to seriously engage with this urgent challenge.

Dear Reader,

If you like our content please support our campaigning journalism to protect health care for all.

Our goal is to inform people, hold our politicians to account and help to build change through evidence based ideas.

Everyone should have access to comprehensive healthcare, but our NHS needs support. You can help us to continue to counter bad policy, battle neglect of the NHS and correct dangerous mis-infomation.

Supporters of the NHS are crucial in sustaining our health service and with your help we will be able to engage more people in securing its future.

Please donate to help support our campaigning NHS research and journalism.