For many years now proponents of “alternatives” to the publicly-funded and largely publicly-provided NHS have been cheerleaders for social insurance systems in other countries as a way to deliver healthcare to the masses.

This is the line taken by speakers from the obscurely-funded right wing Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) and the equally obscure ‘1828 Committee’, whose key parliamentary supporters include the failed Tory PM Liz Truss.

The 1828’s ‘Neoliberal Manifesto’, published jointly with the Adam Smith Institute in 2019, condemns the NHS’s record as “deplorable” and states:

“We believe that the UK should emulate the social health insurance systems as exist in countries such as Switzerland, Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany … among others.”

Politicians backing such systems are looking for ways to minimise public sector funding and maximise the role of the private sector. They argue that the NHS as launched in 1948 is ‘out of date’ – but want to replace it with a social health insurance system … dating back to 1883!

So how do these social insurance systems stack up under analysis? Are they really what we should aspire to?

Germany: analysis of the arguments

Dr Kristian Niemietz of the IEA, argues Germany could be a blueprint for reform in the UK, claiming social health insurance systems tend to have “better healthcare outcomes.”

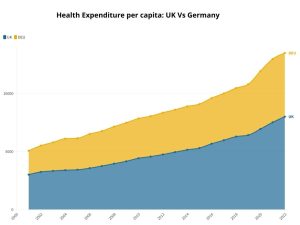

Of course outcomes are related to inputs, and Germany spends a lot more than the UK on health and has done for a very long time.

Misleadingly, the BBC’s Hugh Pym asserts: “Funding of the two systems is similar. Germany spent just under 13% of its gross domestic product on health in 2021 … The equivalent figure for the UK was around 12%.”

But what really matters in terms of resources on the ground is not the share of GDP spent on health (which has been recalculated several times since 2009), but the amount spent per head of population.

On this measure, UK spending is much lower than many of the countries that appear to be delivering better health outcomes. OECD figures show that Germany for example spent 46% more per head on health than the UK in 2019.

So it’s no real surprise to find that after several decades of much higher spending on health, Germany is much better equipped to deliver good outcomes, with 55% more nurses per head and three times as many hospital beds.

The German system is also a two-tier healthcare system, not universal healthcare: around 10% of the population who exceed a certain income threshold may choose to stay with the main system or opt for private health insurance (PHI), which is provided by 41 insurance companies. PHI covers around 10% of the population, including civil servants. Another 4% (e.g. military) are covered through special schemes.

Another important difference is that social health insurance schemes are largely funded by payroll taxes levied on the employed workforce (and their employers) – so many very wealthy people, who live off unearned income (shares, rents, or inherited wealth) and are not on company payrolls make no contribution to the wider pool of health insurance. This is much less fair than a system funded through general taxation levied on the whole population.

Nor is health care free to access in Germany. It is one of the systems that levies a fee for hospital care: adults have to pay €10-15 per day, up to a maximum of 28 days in a year.

Finally, critics of the NHS claim it is plagued by bureaucracy, but argue for European systems which require a much larger and more complex bureaucracy. Germany’s health insurance system, for example, consists of 110 sickness funds – each with its own administration and overhead costs.

And what about other countries

Switzerland, Belgium, and the Netherlands (the other countries cited as preferable models by the IEA and by Truss and her ‘1828 committee’ colleagues) also spend significantly more per head on health than the UK.

Switzerland is the highest spending country after the US, and spent 58% more per head on health than the UK in 2019; Belgium spent 22% more; and Netherlands 29% more per head.

Not only do these countries spend more, they also leave patients stuck with more of the cost of care. Switzerland is one of the wealthiest countries in Europe, yet the proportion of private ‘out of pocket’ spending on health is exceptionally high at 26% of total health spending.

Low and middle income Swiss households pay a higher proportion of their income for healthcare than the richest. Patients wanting healthcare have to pay a “deductible” (fixed amount to be paid before insurance cover begins to reimburse costs) as well as a co-payment (a percentage of the cost of treatment) which cannot by law be covered by insurance. There is a £12 per day fee for hospital inpatient treatment.

Belgium, with slightly higher population than London, levies high user charges for mental health and dental care, again limiting accessibility especially for the poorest.

Mandatory and voluntary health insurance in the Netherlands dumps costs disproportionately on poorer people: even the right wing US Heritage Foundation admits low and lower-middle income individuals end up paying between 20-25% of their income in healthcare costs. The Dutch system offers 1400 different insurance packages, making “choice” for consumers extremely complicated.

The right wing’s ideal models aren’t so ideal after all. But those arguing for them insist, against all of the evidence, that our own NHS is an ‘insurance system,’ funded by National Insurance. This is downright dishonest.

Only in exceptional circumstances have governments turned to use National Insurance money to fund the NHS, which from the outset was mainly funded from general taxation – effectively sharing the risk and the costs of ill-health across the whole tax-paying population, the widest possible pool.

Aneurin Bevan, the Labour minister who pushed through the legislation to establish the NHS in the teeth of opposition from the Tories (who voted 21 times against it), clearly rejected any notion that the NHS was an insurance scheme and insisted it was not linked with National Insurance.

Why propose a social insurance system in the UK?

So why are right wingers so keen to suggest that the NHS is an insurance scheme? Because maybe they want to involve private firms in the provision of ‘social’ health insurance.

Of course the private insurance industry has no interest in chipping in to the cost of running the NHS – or indeed in paying out for patient care if they can possibly avoid it, which is why they are so reluctant to insure older people and those with pre-existing conditions who are more likely to be making a claim.

Bringing them in would not so much be changing the mechanism of funding, much more privatising and commercialising the provision of health care — again to the benefit of the rich, and disadvantage of the poor.

Not an answer to NHS pressure

Social health insurance is not the answer to any of the big questions facing the NHS. It would not cut waiting lists, solve staff shortages, increase NHS capacity, improve outcomes or end the queues of ambulances outside A&E, or the long delays accessing mental health care.

In 1948 The NHS moved decisively beyond the social insurance system that had prevailed from 1911, and established a new, better model of service that allowed patients to access services regardless of ability to pay.

Nobody but the crackpot right wing of the Conservative Party and furtively funded lobby groups now wants the discredited old system back.

Some more history

Social health insurance began in Germany as workplace health insurance, covering only the elite workers in the initial schemes, and only while they were working: it did not cover their families, retired workers or of course the millions of people, working or unemployed, who were left outside the scheme.

It inspired the limited National Insurance system, introduced in 1911, that prevailed in Britain prior to the establishment of the NHS.

By 1946 it left 60% of the population without adequate access even to primary health care. German and other social health insurance systems did eventually develop towards universal health systems – as they were extended to cover the other groups through increased levels of tax funding (i.e. become more like the NHS).

Useful resources

Dear Reader,

If you like our content please support our campaigning journalism to protect health care for all.

Our goal is to inform people, hold our politicians to account and help to build change through evidence based ideas.

Everyone should have access to comprehensive healthcare, but our NHS needs support. You can help us to continue to counter bad policy, battle neglect of the NHS and correct dangerous mis-infomation.

Supporters of the NHS are crucial in sustaining our health service and with your help we will be able to engage more people in securing its future.

Please donate to help support our campaigning NHS research and journalism.