Last month a report from Age UK, ‘The Longest Wait,’ highlighted the extraordinary growth of delays in treatment for older patients requiring emergency admission to hospital. A box on page 5 summarising key statistics makes shocking reading. It reveals:

- There has been a 525-fold increase in the number of instances of corridor care (also known as “trolley waits”) of 12 hours or more since 2015/16.

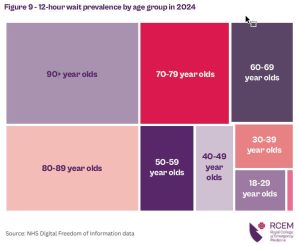

- 1.15 million people aged 60+ waited 12 hours or more in A&E to be admitted or discharged home in 2024/25.

- 1 in 3 (32%) of patients aged 90+ waited for 12 hours or more in A&E to be admitted or discharged home in 2024/25 [that is 149,293 people].

- Two-thirds (67%) of nurses who responded to a survey from the Royal College of Nursing said they deliver care in overcrowded and unsuitable places every day.

Although Labour is the government taking the blame as winter sets in again, Age UK points out that the underlying problem arises from long-term neglect:

“Underinvestment in hospitals over the last fifteen or so years has led to fewer available beds and diagnostic equipment (such as scanners) per patient:

“The number of hospital beds in England is the same as 10 years ago, despite our population ageing and growing, increasing demand.”

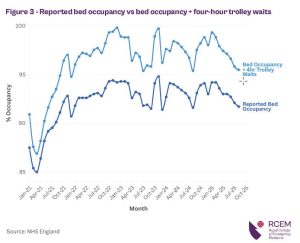

The Royal College of Emergency Medicine (RCEM) has continued to argue that occupancy levels above 85% mean hospitals are overfull and unsafe, since this leaves no flexibility for any surge in demand, which normally occurs in winter. It notes “Bed occupancy has exceeded the safe threshold of 85% for years, averaging 93.1% in 2025.”

However, even these figures seem to be an understatement. One respondent to RCEM’s snap clinician’s survey pointed out that: “Delays for admission [are] hidden by [a] large trolley base. Currently 22 [patients] waiting for beds.” The RCEM explains:

“As the graph above shows, in December 2022, bed occupancy sat at 94.4%, a figure that is already dangerously high. However, when taken together with four-hour trolley waits, this reaches 99.8%. Without an ounce of leeway or respite, a system running this hot is simply not safe for patients or staff.”

This situation is made worse by the large numbers of beds (nearly 13,000 – more than 1 in 8 of the 101,000 beds available in October) that are regularly being occupied by patients medically fit for discharge but unable to leave hospital: the most recent figures, as winter takes hold, show that almost one in five (19.9%) of occupied front line beds had been occupied by the same patients for over three weeks.

Treatment in corridors

The combination of lack of beds, lack of sufficient care outside of hospital, and large numbers of patients in need of admission has meant many (1.7 million people in 2024) have been kept waiting for hours and days on trolleys in corridors or improvised spaces (including at least one former Costa coffee lounge). A survey of Emergency Department Clinical Leads in summer 2025 found that almost one in five ED patients were being cared for in corridors.

For the patients dumped there for hours (or days) on end, corridor care is dangerous as well as demeaning. A further RCEM survey of 58 Emergency Department clinicians in August 2025 found 74% (43) reported care in “non-designated areas,” – and 78% (45) reported patients coming to harm.

The RCEM has revealed evidence that delays in excess of 8 hours before the patient is properly settled in a bed on a ward carry a real risk to life, with up to 300 deaths a week in 2023 associated with long A&E waits.

Pressure on staff and facilities has remained high right through the traditionally quieter summer months. In the year to October, an average of more than one in ten Type 1 emergency patients (those with the most serious needs) were still on trolleys waiting for a bed more than 12 hours after arriving at hospital.

Less sick – less delays

In stark contrast, over the same 12 months, the proportion of patients with the least serious issues (Type 3 attendances) who were seen, treated and discharged within 4 hours ranged from 96.2% to 97.4%; less than 4% were delayed.

By contrast, almost ten times as large a proportion – between 37% and 45% of the most seriously ill patients wait over 4 hours.

It is the much higher performance levels for patients with the lowest level of need (who make up almost half (47%) of the total attendances) that inflate the overall average performance, and give deceptively positive overall figures. That’s why the latest statistics show that in October, for instance, an overall average of 74% of A&E attendances were dealt with within 4 hours – almost on the current reduced target (the previous target, 95%, has been effectively forgotten).

But the grim reality for the most serious Type 1 patients was an average of just 60% – and there is no target or plan to improve on this.

Of course, the 60% figure is also an average, concealing higher and lower figures: a closer look reveals 19 of England’s 42 Integrated Care Boards had figures averaging below 60%, and four (Humber & North Yorkshire, Nottingham & Nottinghamshire, Shropshire, Telford & Wrekin and Stoke on Trent & Staffordshire) averaged below 50%.

Digging down to trust level, performance in half (62 out of 120) of main Emergency Departments was below 60% of Type 1 patients treated and admitted or discharged within 4 hours, with 23 (almost one in five) below 50%, and at the bottom Hull University Hospital (40.9%) and University Hospitals Plymouth (40.6%) just clambering above 40%. These levels of performance for the most seriously ill patients should not be ignored.

Unfair access to treatment

The government also claims to be driven by a concern for inequalities, but queues for treatment in Emergency Departments tend to be drawn from the most deprived and vulnerable sections of society. Another recent report, ‘Corridor Care,’ published by the All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on health, points out the contrast:

“In the South East of England, an average of 62.9% of patients were seen within four hours in 2024, whereas in the North West of England, only 55.5% of patients were seen within four hours on average. The North West of England also had the highest percentage of 12- hour waits last year, with 15.5% waiting at least this long, whereas in the South East of England, this figure was 9.4%.”

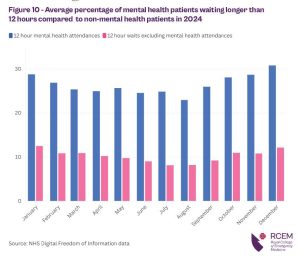

The three largest age groups facing long delays in Emergency Departments are the over-80s, over-90s and over-70s. But another important vulnerable group that tends to face the longest waits of all are people in distress seeking mental health treatment, for whom all too few Emergency Departments have sufficient (if any) support available:

“Mental health patients were 2.5 times more likely to wait 12 hours than non-mental health patients last year. Mental health patients are some of the most vulnerable patients who visit A&E, so it is likely that such long waits – especially in a hospital corridor – would cause them significant distress and potentially lead to their mental crisis becoming more acute.”

The APPG report sums up:

“Corridor care then is disproportionally putting the most clinically vulnerable patients in conditions that nobody should be forced to endure. […] Corridor care has become the most visible sign of system-wide undercapacity in the NHS. It is unsafe for patients, damaging to staff, financially wasteful, and erodes public trust in emergency care.”

Policy not focused on the sickest

However, rather than heed these warnings and take action to change the system to ensure the most serious cases receive timely treatment much more quickly, Wes Streeting and his fellow ministers have picked up where the Tories (and every previous government since Thatcher) have left off – and focused almost exclusively on the patients with the least medical need.

This makes no sense, whether as ministers they are looking to fulfil Labour’s election pledge to get the waiting list back down (and waiting times reduced so that 92% of patients are again treated within 18 weeks of referral) or whether they are concerned at the likely tide of negative press stories about the state of emergency services.

The constant pressure on beds from large numbers of patients needing to be moved out of A&E impacts on, and impedes the ability to expand and sustain higher levels of elective treatment. This cannot be altered by any amount of tinkering with care for minor Type 3 A&E attenders.

Minor cases can move through quickly because they do not require the services that are most overstretched and underfunded.

Indeed, even if a handful of Type 3 emergency patients were to be kept waiting longer than 4 hours, NONE of them would need a bed or make any demands on operating theatres. NONE of them are dumped in corridors or left waiting for days on end. And none of them wind up stuck in beds on acute wards, despite being ready for discharge from hospital, because there is no suitable support available for them.

Spending time and effort (and quite possibly significant amounts of limited public funding) trying to divert these minor cases away from the hospitals, where they tend to go by default, and into “neighbourhood health centres” – that have yet to be built – is likely to prove a frustrating failure, just as ‘polyclinics’ and a host of variously named ‘minor injury units’ have all failed over the past 30 years or more to show themselves to be effective, efficient, or value for money.

And while all this same old nonsense is being rolled out once again, the visible problems of the Emergency Departments continue to worsen, as the trolleys line up along corridors, commandeer other areas, and bring their own predictable dangers and discomforts to patients.

Calls for action

Age UK says 93% of its supporters think that ending corridor care should be the top priority, or one of the top priorities, for the government. The Royal College of Nursing, other health unions, the RCEM, and almost anyone who has spent a moment thinking about priorities will agree with them.

NHS statistics show there has been a near 10% increase in England’s population since 2011: this alone would suggest increased need for investment to ensure emergency services can cope.

But the increase in the caseload arriving at Emergency Departments has been much higher – with almost 6 million more A&E attendances (just over 27% increase) in the same period. This is substantially driven by the increasing proportion of the population who are elderly and in poor health.

The RCEM (who researched and funded the APPG report) argue that, while an extra 8,000 beds are needed to reduce occupancy levels to 85%:

“this could be achieved without opening new beds. So far on average in 2025, 13,000 beds (13% of the total bed base) were occupied by patients medically fit for discharge but still remained. Freeing just 60% of these beds would bring occupancy to safer levels and ease pressure on EDs.”

The British Geriatrics Society (BGS, ‘the UK’s first and only membership organisation of multidisciplinary professionals with an interest in improving healthcare for older people’), endorsing the APPG report, spells out a combined operation that is needed.

On the one hand, “Flow through the hospital needs to be restored, in part by addressing the lack of community-based rehabilitation and social care that means 13,000 people remain marooned in hospital when they are medically fit to be discharged.”

The Lowdown has recently highlighted the cost to the NHS of delayed discharges from acute wards.

But in addition, the BGS says there must be resources targeted on the number of admissions of frail older people who can be the hardest to discharge, including a new triage system that can identify the older patients who are likely to need more support:

“We also need more community-based care to reduce avoidable Emergency Department attendance. Front Door Frailty services are a highly effective way of identifying and supporting older patients who arrive in the ED, and reducing admissions that can turn into long hospital stays. These approaches require a workforce that is skilled in supporting the complex needs of older people with multiple long-term conditions, including frailty and dementia.”

All of the recent reports on corridor care share one obvious conclusion: that if the government and NHS continue to ignore the problem and fail to invest in improved systems to end it, they will continue to fail the most vulnerable patients – and fail on other targets such as productivity, elective waiting times and public satisfaction.

Failure on these crucial issues, plus a winter of awful headlines on the state of our emergency care would scupper Wes Streeting’s ambitions of becoming Labour leader. But will that be enough to make him take notice?

STOP PRESS: As this article is completed (November 20) the Health Service Journal has just flagged up new alarming provisional figures from the NHS revealing the performance of trusts and their individual emergency hospitals on the most serious emergency patients – which tell another shocking story. Just 30 per cent of admitted A&E patients in October were dealt with in four hours. 35 trusts met the 4-hour standard for less than 20 percent of admitted Type 1 and 2 patients in October, with 3 of these delivering below 10 percent.

And NINE hospital sites dealt with 10% or less of admitted Type 1 and 2 patients within 4 hours: Southport and Formby DGH (Mersey and West Lancashire Teaching Hospitals) 3.6%; Diana Princess of Wales Hospital (North Lincolnshire & Goole FT) 4.7%; Alexandra Hospital (Worcestershire Acute Hospitals) 6.4%; Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Woolwich (Lewisham & Greenwich) 6.6%; Wexham Park Hospital (Frimley Health FT) 6.6%; Warrington Hospital (Warrington & Halton THFT) 8.5%; Basildon Hospital (Mid & South Essex FT) 8.8%; Colchester Hospital (East Suffolk & North Essex FT) 9.2%; and Kettering General Hospital 10%.

HSJ notes that the new data “indicates the improvements in overall four-hour performance … have been mainly in patients not deemed ill enough to require admission.”

Dear Reader,

If you like our content please support our campaigning journalism to protect health care for all.

Our goal is to inform people, hold our politicians to account and help to build change through evidence based ideas.

Everyone should have access to comprehensive healthcare, but our NHS needs support. You can help us to continue to counter bad policy, battle neglect of the NHS and correct dangerous mis-infomation.

Supporters of the NHS are crucial in sustaining our health service and with your help we will be able to engage more people in securing its future.

Please donate to help support our campaigning NHS research and journalism.