The spread of the Covid-19 variant, Omicron, across the world, is a reminder that mass vaccination programmes have failed to reach a large proportion of the world’s population; Covid-19 has continued to spread out of control allowing numerous mutants to develop and the oft-used phrase no-one is safe until we are all safe is proving very apt indeed.

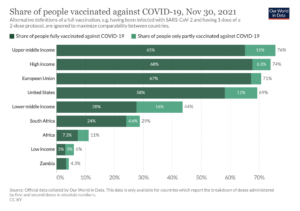

But it did not have to be this way – the world has produced more than enough vaccine to vaccinate the global population. Why this has not happened is down to the inequitable distribution of vaccines – the high income G20 countries, including the US, the EU, and the UK have used or hoarded 89% of all vaccine produced. This has enabled them to undertake mass vaccination campaigns that are now into giving third or booster vaccinations. In contrast, poorer nations have not reached 30% vaccination rates and in many cases are much lower (fig 1). By the end of November, South Africa had managed to fully vaccinate just 24% of its population and Africa as a whole was at 7.3%, with several countries within the continent at much lower rates of vaccination.

Yet in 2020, Covax was created, a scheme run by UN agencies, including UNICEF, and the World Health Organization (WHO), to ensure that Covid vaccines are made available around the world, with richer countries subsidising costs for poorer nations. COVAX’s initial target was to distribute enough vaccines to protect at least 20% of the population in 92 low- or medium-income countries – starting with healthcare workers and the most vulnerable groups.

Additional pledges were then made in June 2021 at the G7 summit in Carbis Bay, UK, and in September 2021 at the Global COVID-19 Summit. At the summit the WHO, the Group of Twenty (G20), and other participants endorsed the goal of achieving 40% vaccination coverage in every country by the end of 2021, and 70% coverage by mid-2022.

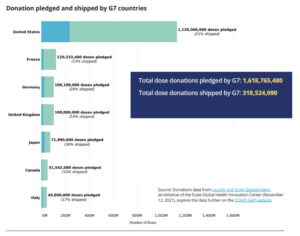

The vaccine pledges hit the headlines, but the actual vaccine doses have not reached the target countries in sufficient amounts to make any dent in the pandemic.

The recently released report Holding the World to Account: Urgent Actions Needed to Close Gaps in the Global COVID-19 Response – produced by COVID GAP, an independent organisation based at Duke University, USA, notes that taken together, the G7 countries have shipped about 319 million donated doses by November 2021, which is only about 20% of what the countries had collectively pledged (Fig. 2).

Based on current vaccination rates, nearly all low-income countries, including most African countries, are not on track to reach the 40% vaccination target by the

end of 2021. In contrast, almost all (96%) high-income countries have already achieved 40% coverage, and most are far beyond this target. Among the 92 countries covered by the COVAX Advance Market Commitment (AMC92 countries), a system to supply countries with vaccine pledged by high income countries, the median vaccination coverage is just 11%.

The COVAX GAP report notes that:

“With less than seven weeks left in 2021, the outlook for these countries is grim. The 40 percent vaccination target will not be reached during 2021 or even by early 2022

without a clear action plan at local, regional, and global levels, significant increases in vaccine supplies, and the resources and capabilities to distribute and use them.”

The COVAX GAP report notes that the 40% target requires 650 million doses of vaccine can be achieved by the diversion of vaccine away from the G7 and EU countries to lower income countries. The team at COVID GAP has calculated that if all the excess doses available in G7 and EU countries (834 million doses) were to be diverted to low-middle income countries (LMICS) there would be enough vaccine to fully close the 650 million dose supply gap.

This diversion could be achieved by “queue shifting” – when developed nations defer delivery of their supplies so that they can be sent to lower income countries. The US has recently deferred delivery of some of its contracted Moderna doses to prioritize dose delivery to the African Union and at the end of November, Switzerland agreed to move further down the queue for delivery of the Moderna vaccine. Now 1 million doses of the Moderna vaccine originally planned to be delivered to Switzerland will instead be made available to COVAX. Switzerland will then take COVAX’s place in the queue, and receive these doses later in 2022. Although a good move, it is not nearly enough.

The reluctance of rich countries to donate vaccine, despite pledges to do so, is not the only issue with the COVAX system.

The majority of the donations to-date have been ad hoc, provided with little notice and short shelf lives, it has been severely challenging for countries to plan vaccination campaigns. Under these circumstances it would be difficult in developed nations, but in countries with limited healthcare systems, poorly developed cold chains and transportation networks, then the burden becomes almost impossible. The African Vaccine Acquisition Trust (AVAT), the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) and COVAX have jointly called for the quality of donations to improve, with not just vaccine donations but other essential supplies, such as syringes. The countries need a predictable and reliable source of vaccine that can be used for a long-term sustainable vaccination programme.

It is clear to many that the COVAX system, which relies on the generosity of the governments of rich nations, is never going to solve the issue of Covid vaccination for Africa or any other poor nation. But there is another way – give these nations the ability to make the vaccines themselves. Countries such as South Africa and India have the infrastructure to manufacture the vaccines, the only thing standing in their way is intellectual property rights (ipp or patents) and a lack of help from the innovator pharmaceutical companies.

In late 2020, India, the country in the best position to increase vaccine production quickly, and South Africa introduced a proposal to temporarily waive intellectual property rights on COVID-19 vaccines and therapies at the WTO (World Trade Organisation), but negotiations became deadlocked in the face of opposition from many developed countries. More than 100 countries backed the waiver saying it will save lives by allowing developing countries to produce COVID-19 vaccines. But a handful of countries, including the EU and the UK, and some hosting major pharmaceutical firms such as Switzerland, were opposed.

In May 2021, hope was kindled that patents covering the vaccines would be waived, when the US administration said it backed a temporary waiver of international patent protections for COVID-19 vaccines, but little progress has been made since.

Pressure has been building over the past few months however. The last few weeks has seen the EU move closer to a deal, according to a Euronews report, which notes that the European Commission is now “ready to go beyond” its initial position, “to get consensus on a waiver that makes sense [and] that will increase production”.

The appearance of the omicron variant led US President Joe Biden to once again call for a waiver on patents. The UK government, on the other hand, continues to be opposed to a patent waiver. When questioned in Parliament recently by Green MP Caroline Lucas, Sajid Javid, the Health Secretary said a patent waiver would not be ‘helpful’.

This week nursing unions in 28 countries filed a formal appeal with the United Nations over the refusal of the EU, UK, Norway, Switzerland and Singapore to temporarily waive patents for Covid vaccines. The letter, coordinated by the healthcare umbrella organisation Global Nurses United, and Progressive International, cited what it called an “immediate threat to people’s right to health”.The appeal noted the lack of a patent waiver had contributed to a “vaccine apartheid” in which richer nations had secured at least 7bn doses, while lower-income nations had about 300m.

At the same time, over 230 public health professionals have also written to The Times urging all countries to waive intellectual property rights, saying that not to do so was “grossly unjust and undermines the international effort to combat Covid-19.”

Negotiations on a targeted waiver were scheduled to begin 30 November in Geneva at the WTO, but the Washington Post reports that due to the Omicron variant, the talks have been postponed with no new date set.

While there was a deadlock between countries on patent waivers at the WTO, there has also been little help for the poorer nations from the innovator pharmaceutical companies, which could just license out their technology and advise on production.

Soumya Swaminathan, the WHO’s chief scientist, asked companies to contribute their intellectual property to the Medicines Patent Pool, an organisation, backed by the UN, which works to bring together innovator companies and reliable manufacturers in developing nations. But according to a recent article in Nature, pharmaceutical companies have refused to join; Thomas Cueni, the director-general at the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers & Associations (IFPMA), cited quality control and quality assurance being an issue with this approach.

The only country that has wholeheartedly shared its vaccine technology is Russia, which has granted a broad license to the Sputnik V vaccine to 34 drug companies outside its borders, including in India and Brazil. However, this is not the easiest of vaccines to make, as the second dose of the vaccine has a different composition than the first and it is proving difficult to produce in large quantities.

With no widespread patent waivers and little to no help from the innovator companies, the developing nations have had to essentially go it alone.

In June 2021 the World Health Organization (WHO), COVAX and a South African consortium comprising Biovac, Afrigen Biologics and Vaccines, a network of universities and the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) established its first COVID mRNA vaccine technology transfer hub. Back in October 2020, Moderna pledged not to enforce its patents during the pandemic and this news, plus a large amount of publicly available information on the Moderna vaccine, meant that the first target for the hub was replication of the Moderna vaccine.

However development has not been easy, the lead company Afrigen Biologics and Vaccines has had to rely on publicly available information, help from the WHO and international consultants, including the US National Institutes of Health, as Moderna has refused to part with any information about how to make the vaccine. As a result, what could have taken one year to complete is now likely to take around three years and there is still uncertainty around what will happen when the team reach phase 3 trials of the vaccine – will Moderna allow them to go ahead?

The severity of the omicron variant and whether the current vaccines will protect against it is, as yet, unclear, but what is clear is that unless rich countries fulfill their pledges to poorer nations and increase the speed of mass vaccination, omicron will not be the last variant to sweep across the globe undermining all our efforts to protect our populations – no-one is safe until we are all safe

Dear Reader,

If you like our content please support our campaigning journalism to protect health care for all.

Our goal is to inform people, hold our politicians to account and help to build change through evidence based ideas.

Everyone should have access to comprehensive healthcare, but our NHS needs support. You can help us to continue to counter bad policy, battle neglect of the NHS and correct dangerous mis-infomation.

Supporters of the NHS are crucial in sustaining our health service and with your help we will be able to engage more people in securing its future.

Please donate to help support our campaigning NHS research and journalism.