The latest raft of performance figures have shown that the NHS is still mired in a chronic capacity problem and hamstrung by the lack of adequate provision of community health and social care to support patients ready for discharge.

The Royal College of Emergency Medicine (RCEM) notes that the final weekly winter ‘situation report’ figures released by NHS England, covering 25-31 March show that major hospitals are “dangerously full”:

The peak occupancy was on March 27, when almost 19 out of every 20 beds across England were occupied – many taken up by people who were well enough to go home but unable to because of the lack of appropriate support. Less than half the patients who were well enough to be discharged did go home each day, leaving an average of 13,690 patients still stuck in hospital bed after a decision to discharge them has been made. A daily average of 18,466 patients occupied a bed for 21 or more days.

The RCEM explains: “Extremely high bed occupancy leads to delays in patients being admitted from Emergency Departments which can result in overcrowding and people having to endure extremely long waits often in corridors on trolleys, as well as delays in ambulances being able to move their patients into A&Es; effectively causing the system to grind to a halt.”

Worse, delays in ambulances outside hospital and in crowded A&E put lives at additional risk. The RCEM estimates that in 2023 there were almost 14,000 associated excess deaths related to waits of 12 hours or longer – more than 268 a week.

The 4-hour waiting times in A&E show only the most minor improvement, with 1.58 million patients waiting over 4 hours in 2023/4, just 80,000 lower than the record year 2022/23 total of 1.66m.

The fourth quarter of 2023/24 was the highest ever fourth quarter for 4-hour delays (and almost double the 2019/20 level), and the Q4 2023/24 total of 141,693 trolley waits of 12 hours plus was the highest ever quarterly level.

Perhaps just as alarming is the low level of the most serious Type 1 A&E patients seen and treated or discharged within 4 hours, which has plunged from an average of around 75% in 2019/20 to an average of just 58% last year, leaving almost 1.8 million patients waiting longer than 4 hours in 2023/24.

Type 1 patients, who are most likely to need admission to a bed, are the ones faced with lengthy trolley waits for a bed to become available. The annual total of almost 444,000 12-hour plus delays last year was 8% higher than 2022/23 – and almost 36 times the total of 12,435 in 2019/20 (not to mention 1,849 times the 240 incidents ten years ago in 2013/14).

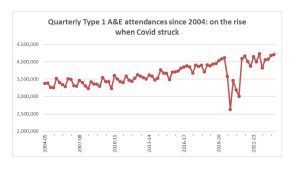

It’s true that, as NHS England was keen to emphasise, the figures are influenced by a growth in total numbers of A&E attendances, which rose last year by 2.5%, and are now at the highest ever, 4.5% higher than the pre-pandemic year of 2019/20. But the proportion of the most serious Type 1 patients is almost unchanged at close to 63%: the big increases in delays clearly stem from inadequate capacity – in both hospital beds and in services outside hospital.

Over all categories of patients England’s hospitals delivered 71.9% seen within 4 hours in Q4 – well short of the optimistic 76% target NHS England had set by the end of the year (itself a far cry from the 95% standard that was set in the 2000s and last achieved in 2014/15) .

The failure now to hit even 76% comes despite NHSE bosses resorting to desperate tactics and impossible demands in their efforts to force an apparent improvement in A&E performance.

On the last day of February trust CEOs and chief operating officers were instructed to sign declarations that their hospitals would meet the target of seeing and treating 76% of A&E patients within 4 hours during March. It was already nigh on impossible for this to happen, given that only 13 trusts in England had met this target in January, and almost all major targets have been missed for the whole of 2023/24.

Definitions of bullying include setting unreasonable or impossible deadlines and setting unmanageable workloads. NHS England is a serial offender: and bullying from the very top is transmitted throughout the NHS. Indeed to add further pressure trust bosses were required to give the direct phone numbers and emails of the senior officers responsible for performance. This would facilitate even more NHS England bullying.

This latest brazen effort to bludgeon trust bosses into line despite resource constraints follows on NHSE instructions earlier in February to focus on speeding the treatment of the least serious ‘Type 3’ A&E patients – to boost the overall figures.

Ever since 2010 the much easier and rapid handling of the most minor Type 3 cases has helped to hold up the overall figures, while the delays have grown in handling the most serious Type 1 patients.

In February 2011 for example (with residual benefit from the previous decade of investment) the average for all A&E attendances was 97.1% treated and admitted or discharged within 4 hours. This included 95.6% of Type 1 and 99.9% of Type 3.

By February 2024, after almost 14 years of real terms cuts, the overall average was just 70.9% within 4 hours, within which 95.2% of Type 3 cases were treated within 4 hours, but only 56.5% of the most serious Type 1 cases.

To focus on Type 3 cases when the situation is so bad for Type 1s indicates that NHS England is not only seeking effectively to falsify the picture by devoting more resources to the patients with the least serious needs, but they are mathematically illiterate: in most cases the existing performance on Type 3 patients is already so good there is little room for significant improvement.

The latest scam was accompanied by financial incentives that would hand extra cash from a £150m ‘incentive fund’ to the best-resourced trusts that achieve the highest 4-hour performance and/or the biggest percentage improvement between January and March.

The winners could gain handouts of up to £4m – while those up against the greatest pressure and most lacking in resources would get nothing.

As we head into a new year of even tighter spending constraints and still-rising demand for emergency services it’s high time for NHS England bosses to face up to the real figures, and speak truth to power on the need for more resources rather than try to bully their way to success.

Opposition parties, too, need to take note that any improvement in these key performance statistics will only come through investment in staff, facilities and equipment, not empty talk of “reform” that annoys everyone in health care and achieves nothing.

Dear Reader,

If you like our content please support our campaigning journalism to protect health care for all.

Our goal is to inform people, hold our politicians to account and help to build change through evidence based ideas.

Everyone should have access to comprehensive healthcare, but our NHS needs support. You can help us to continue to counter bad policy, battle neglect of the NHS and correct dangerous mis-infomation.

Supporters of the NHS are crucial in sustaining our health service and with your help we will be able to engage more people in securing its future.

Please donate to help support our campaigning NHS research and journalism.