John Hutton signed off thirteen NHS Private Finance Initiative (PFI) building projects as a Labour health minister in 2002 (see footnote). Last month he was appointed to speak up for private sector investors ahead of likely disputes as some of the earliest PFI contracts draw to a close.

(Now Lord) John Hutton has been installed as the chair of the Association of Infrastructure Investors in Public-Private Partnerships (AIIP), a body specifically formed to represent the investors’ view.

The private consortia are eager to head off the danger of legal battles over liability for repairs and other costs in the final few years of contracts when the private sector has the least incentive to upgrade equipment or carry out maintenance.

According to the National Audit Office around 70 PFI contracts worth about £4bn are due to come to an end in the next four years, rising to 300 over the next decade. The issue is complex because as the NAO emphasized in a major report in 2020, “the PFI model is designed to be self-monitoring.”

In other words, the private sector itself is left to review performance on contracts and report to the public body concerned, which it does through the company that represents each consortium, known as the ‘Special Purpose Vehicle’.

One of the supposed benefits of PFI has been that the assets – hospital buildings were supposed to be maintained and refurbished throughout the full term of the contract before being handed over to the public sector.

NHS trusts have responded to inadequate government funding and chronic lack of capital by running up an ever-larger backlog bill for maintenance – the latest estimate £11.6 billion, leaving many hospitals with patient treatment areas are being closed “all the time” due to crumbling estates, fire risks and flooding, according to NHS England.

The NAO report warned that unscrupulous private providers may also seek to minimise maintenance in order to maximise their profits, with potentially serious consequences: “The main risk to value for money is that the assets are not returned in a satisfactory condition.”

The NAO warns public bodies to be vigilant, and argues that problems have to be confronted while the contracts are still live:

“PFI providers have an incentive to limit expenditure on maintenance and rectification work in the final years of the contract as any savings can be used to pay out higher returns to investors. … If any contractual rectification work remains outstanding at contract expiry, there are limited options for recourse …”

However it appears this requires a change of attitude: “The public sector does not take a strategic or consistent approach to managing PFI contracts as they end, and risks failing to secure value for money during the expiry negotiations with the private sector.”

A useful new King’s Fund article by former FT correspondent Nick Timmins, focused on the likely legal battles as the private and public sectors clash over responsibility for costly repairs and replacements, has flagged up a report commissioned by the government’s Infrastructure and Projects Authority (IPA).

The White Fraiser report warns that relations between what used to be described as the PFI “partners” have deteriorated so badly that ‘a lucrative and self-perpetuating disputes advisory market’ has been spawned, in which the advisers make things worse by seeking to win for their side ‘at all costs’. Hence the increasingly toxic relationships, with the “health sector, in particular, … having become very adversarial.”

White and Fraiser warn “there is a real risk that the prevalence of major disputes will only increase and, ultimately, become commonplace across the PFI industry.”

In the NHS, as Timmins points out “exit negotiations are still being done by individual hospitals and others, usually by people who have not done this before and are likely only to do it once, while the PFI industry has always been more concentrated and hence more expert.”

This is the context in which Lord Hutton is going in to bat for the private sector.

The first NHS PFI deals were not signed off until 1997, and although Calderdale Royal Hospital’s PFI expires this year, the bulk of them begin to complete from 2025 onwards. Among the significant NHS schemes expiring in the next few years are King’s College Hospital’s Golden Jubilee Wing and the Princess Royal Hospital (PRUH) in Bromley.

PFI contracts are paid off through annual ‘unitary charge’ payments to PFI consortiums, which are legally binding, and cover availability of the building, maintenance and other support services plus interest payments and profit. These payments continue even as the PFI deals draw to a close, and in most cases continue to grow by at least 2.5% per year, or more if inflation is higher.

The service element of the unitary charge paid by hospital trusts in the early PFI schemes (but largely eliminated in subsequent PFI and PF2 schemes) averages out at around 40% of the total payment each year, according to analysis by Mark Hellowell and Allyson Pollock.

The private provision of these services is part of the income/profit stream of the PFI consortium.

The most recent Treasury figures, which appear to be in cash terms, show the average total cost of NHS PFI schemes over their lifetime is seven times the initial construction cost, and excluding the cost of services the average is four times the original cost of the building.

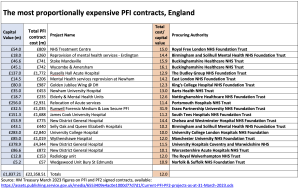

Some are much cheaper, costing the same or less than a conventional 25-year mortgage at 6% interest (in which total payments roughly double the initial value). But 20 of the 121 NHS schemes in England will have paid out more than TEN times the initial cost [See table below].

The PRUH cost £123m to build, but the final four unitary charge payments up to expiry in 2027/28 add up to £178m, almost half as much again (and could be further increased by inflation). The total of PRUH payments as projected by the Treasury is £910m – over seven times the initial cost. Even if the average 40% cost of support services is excluded, the payments on the hospital itself still come out at £546m – 4.4 times the initial cost.

Many schemes are much more expensive. King’s Jubilee Wing may have only cost £80m to build, but the Treasury prediction of the final four unitary charge payments to expiry in 2027/28 adds up to £238m – almost three times the cost to build it in the first place. The total cost is £987m, 12.3 times the initial cost. Even deducting 40% for support services leaves a cost of £592m for the building, well over seven times the building cost.

King’s is an example of extremely poor value PFI deals: the biggest cost overall in this select group of hyper-expensive deals is the £4.3 billion total bill to be paid for the £379m University Hospital Coventry & Warwickshire – 11.5 times the initial investment.

Some of the worst NHS schemes began with such a small cost they should have been affordable without PFI, but have wound up costing hundreds of millions. The most astonishing is the Runwell Forensic Medium & Low Secure unit, costing a total of over £1 billion – a staggering 32 times the original £32m investment.

Several other mental health schemes are also among the very worst value PFI deals: here the use of PFI indicates the lack of NHS capital to cover even small schemes in mental health.

In the main NHS schemes have been an index-linked cash cow for PFI consortia, with many if not most of the profits flowing to offshore tax havens.

So there is no excuse for the private sector cutting back on maintenance or replacement of clapped out equipment or fittings: doing so is simply driven by greed for even higher profits at the expense of the NHS and its patients.

Sadly the private firms, now led by Lord Hutton, are able to take advantage of too many ill-prepared public sector bodies. The NAO survey of 571 PFI schemes in England and 129 in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland found some paying little attention, and others being kept at bay by PFI firms exploiting contract restrictions:

“30% of survey respondents were not monitoring annual maintenance spending, and 50% did not maintain an asset register. … Around 35% of respondents stated they had insufficient access rights to monitor the maintenance programme adequately.”

The NAO found evidence that PFI investors and sub-contractors were not cooperating with authorities to provide information – one in five survey respondents who had asked for information “considered the contractor had been uncooperative, with data requests being ignored or denied on grounds of not being a contractual obligation.”

There is also worrying evidence from the PFI deals that have already expired, in which almost half (four out of nine) survey respondents were “unsatisfied with the condition of the assets they took ownership of at expiry.”

Despite advice of the Infrastructure and Projects Authority to begin preparations seven years ahead of contract expiry almost a third of respondents told the NAO they lacked sufficient staff, a quarter lacked the necessary skills … and 60 percent said they planned to hire management consultants, another hidden cost of PFI.

The Financial Times reported that Lord Hutton’s new role would be to chair an organisation “formed to defuse disputes between investors and public sector over financing deals,” but it’s clear from the outset which side of the fence he is on: and it’s not the public sector.

He showed his hand when earlier this month questions were raised by the BBC about new figures revealing the soaring costs and alarming consequences of PFI school contracts. Examples were given of school leaders facing at least a 10 per cent increases in charges, and at least one school now spending nearly 20 per cent of the school’s entire budget on meeting “frustrating” terms of its PFI contract, which had risen by 47% since 2021.

The National Education Union (NEU) estimates PFI schools are haemorrhaging around £400m annually in interest charges alone.

The PFI bosses’ response came from Lord Hutton, who blamed inadequate school budgets and told the BBC the contracts “do reflect good value for money for the taxpayer” and “make sure that schools are getting value for money when it comes to cleaning, catering and everything else.”

So the big question is if Hutton is on the case for the PFI leeches, who is fighting the corner of the NHS and the rest of the public sector?

* Of the thirteen PFI projects apparently signed off by John Hutton in 2002 three escalated in cost so far they have still not been built. Two of these (Leicester and Whipps Cross in North East London) have notionally been included in the empty promise of “forty new hospitals,” while the third, St Mary’s in Paddington has – despite its dire state of repair and massive maintenance backlog – been postponed until after 2030. The eventual capital costs of all the other projects (with the exception of Hull) were all substantially above the amount signed off by Hutton, with two (North Middlesex Hospital and the Oxford cancer project) coming in more than double the expected cost – before the index-linked PFI payments further inflated the costs.

Dear Reader,

If you like our content please support our campaigning journalism to protect health care for all.

Our goal is to inform people, hold our politicians to account and help to build change through evidence based ideas.

Everyone should have access to comprehensive healthcare, but our NHS needs support. You can help us to continue to counter bad policy, battle neglect of the NHS and correct dangerous mis-infomation.

Supporters of the NHS are crucial in sustaining our health service and with your help we will be able to engage more people in securing its future.

Please donate to help support our campaigning NHS research and journalism.