Resident doctors’ strikes are happening for reasons beyond pay. While Wes Streeting says there can be no better than a 2.5% pay rise in 2026—below inflation—this weakens the idea that ministers want to restore doctors’ pay to its former value. The real issue is deeper: growing doctor unemployment, fewer training opportunities, and the added stress on doctors in hospitals and clinics.

Despite the much-vaunted ‘Long Term Workforce Plan,’ published in June 2023, and the Labour government’s promise in the 10-year health plan (10YHP) to produce a new ‘10 Year Workforce Plan for the NHS’, it is clear England’s NHS – and indeed the NHS across the UK – has got a number of issues seriously wrong.

With an alarming proliferation of ‘corridor care’ and long delays in treating emergencies, a waiting list above 7 million, disastrous delays in mental health care – even for children — and patients demanding swifter access to primary care, we now have the phenomenon of unemployment amongst resident doctors and fully qualified GPs. Thousands of doctors are also blocked from becoming consultants by the inadequate number of specialist training posts.

Similar problems also affect other professional staff: even with maternity units crying out for staff, newly-qualified midwives are struggling to find posts offering a period of “preceptorship” – a period of supervision and support to equip them to develop the confidence and experience to act independently when required in delivery suites and in the community.

It seems our short-staffed, cash-strapped NHS has, in many areas, reached the point of having too few staff in post to allow it to recruit (and, where necessary, complete the training of) the extra professional staff it needs.

The current system does not effectively match the number of graduating medical or midwifery students with the number of training or preceptorship posts.

More planning is being put in place (e.g., workforce modelling, new posts being commissioned). But the evidence suggests those systems are insufficient or under-resourced compared to the scale of growth and demand.

The result is frustration and anger over wasted time and energy, as graduates who have already invested years in learning vital skills and knowledge hit a brick wall and cannot progress.

Consultant vacancies

There are still gaps at the top of the medical profession: a new report by BMJ Careers has found that some NHS organisations have as many as one in three consultant posts vacant, and these vacancies are expensive. In England, Scotland and Wales, NHS bodies spent £674m on locum consultants in 2024/25.

The Royal College of Physicians’ (RCP) latest Focus on Physicians Survey tells a similar story: it found 59% of consultants reported vacancies at their own grade, with 83% concerned that rota gaps are having a negative impact on patient care. Moreover the consequences have a political and financial cost: the most common consequences of consultant-level rota gaps were said to be reduced access to out-of-hours inpatient care (39%) and longer hospital stays (28%).

The Royal College of Anaesthetists (RCoA) reports 89% of clinical leaders who manage anaesthetic departments across the UK say that elective surgery is being delayed because of a shortage of anaesthetists, with 43% saying this happens on a daily or weekly basis. Over two thirds (68%) of clinical leaders say that increasing the number of anaesthetists would do more than any other measure to reduce waiting lists – ahead of factors such as ward space (50%) or operating theatres (42%).

The report also shows that while there are more anaesthetists now than in 2020, greater demand and long waiting lists mean the shortfall has increased from 1,483 in 2020 to 2,147 in 2025 (15% below what is needed).

The impact of some other specialist consultant shortages is also severe. Almost nine in ten (86%) of small cancer centres – and almost two thirds of all cancer centres – had consultant vacancies unfilled for 12 months or more, while almost a quarter (23%) had reported vacancy freezes in 2024. Seven in ten (70%) of cancer centre leaders were concerned by the effects of increased workload and staff shortages on patient safety.

One resident doctor at a north London trust told the researchers of the impact of consultant shortages:

“It’s a complete nightmare – the doctors who are left working have to work at 150%, patients have to wait longer to be seen, and by the end of the shift doctors are running on fumes.”

61% of NHS recruiters said consultant vacancies were having a significant negative impact on waiting times, and over half (51%) said they expected the need to recruit consultants will increase in the next year: however slightly more (52%) said they expected their recruitment budget to decrease, with only one in 20 expecting any increase.

Many of the bodies with highest rate of consultant vacancies are mental health trusts, with England’s highest vacancy rate in Lincolnshire Partnership FT, at 36%. The average mental health consultant vacancy rate is 15.6%, double the average for acute trusts (7.7%).

More broadly, half (49%) of all NHS organisations across the UK have more than 10% consultant vacancies. The greatest impact of these vacancies is on staff workload and wellbeing, followed by waiting times, quality of care, patient experience and patient safety.

Numbers of resident hospital and community doctors in the NHS have gone up by 44% since 2016, a bigger increase than the numbers of consultants (up 38%). And large numbers of International Medical Graduates (IMGs) are also lengthening the odds against home grown medical students progressing in their chosen career.

While overseas doctors play a vital role in the NHS, excessive reliance on staff trained abroad threatens to strip key professionals from their own countries, weaken health care systems, and limit the expansion of training in the UK.

Chaos in resident doctor training

The route to a consultant post has to be through years of work as a resident doctor, gaining practical experience as well as knowledge: but for this to happen there needs to be enough training capacity in place.

The RCP is calling for an “urgent expansion” in medical training places in England, and “sustainable, long-term workforce planning with clear projections for the number of consultants and specialist doctors needed to meet future patient demand,” after new NHS figures revealed a 42% increase in competition for certain posts in 2025.

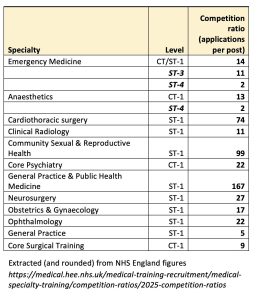

The latest official NHS statistics show the numbers of applications per training post in some key specialties are dauntingly high: 14 seeking every basic emergency medicine post; 17 applying for every starter post in obstetrics and gynaecology, 22 in psychiatry, 27 in neurosurgery, 74 in cardiothoracic surgery and 98 in community sexual and reproductive health.

In some cases the level of competition gets easier at later stages for those who do get a foot on the ladder (Anaesthetics training posts begin at 12.5 applications per post but by ST-4 the numbers have thinned out to average less than two per post.) (see table) However this is not much consolation for those who find they cannot get near the bottom rung of the ladder.

The RCP reveals that there were 8,841 applications for internal medicine training (IMT) – the first step to becoming a consultant physician – for 1,678 posts in 2025. This is compared with 6,237 applications for 1,698 posts in 2024, meaning the competition ratio increased from 3.69 to 5.27.

The data sends a “deeply worrying message to the next generation of doctors”, according to the RCP, which has concluded the current system is “no longer fit for purpose,” because “Chronic bottlenecks” in their training have left many resident doctors worried about their future in medicine.

The RCP national ‘next generation’ survey of resident doctors reveals:

- Less than 1 in 5 (17%) think that postgraduate recruitment processes are fair

- Most (72%) cited insufficient staffing and rota gaps as the biggest negative impact on training quality and wellbeing, followed by high clinical workloads (66%) and poor IT (59%)

- Only 65% of respondents expect to still be working in the NHS in 5 years.

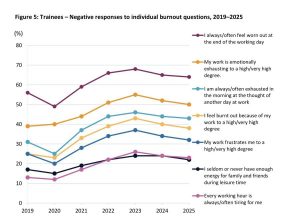

The RCP survey results paint a stark picture of training being delivered “in an environment of rota gaps, relentless service pressures and widespread burnout.” Many resident doctors described training as ‘tick-box’, ‘inconsistent’ and ‘eroded by service provision’.

The RCP warns that without urgent action, the NHS risks losing a generation of talented doctors, as systemic pressures erode both training quality and resident doctor wellbeing, leaving many feeling undervalued.

Across the whole spectrum of medical training, the situation is even worse, and worsening. Data from the BMA shows 91,999 applications were made for 12,833 specialty training posts in England in 2025, resulting in an overall competition ratio of 7.17 applications per post.

This is a sharp rise from 4.7 applications per post in 2024, and more than triple the 2019 level of 1.9. The situation has been worsened by the total number of applications – boosted by overseas applicants – increasing by more than 30,000 (54%) in a single year, while the number of available posts only increased by 90.

The tough numerical competition creates a serious bottleneck in the training pathway, leaving many resident doctors “in limbo,” facing career uncertainty or even unemployment after completing their foundation training.

Small wonder then, that in a BMA survey of 4,401 doctors, who were asked whether they have substantive employment or regular locum work from August 2025 half (52% of the 1,062 FY2 doctors who responded) said they did not. Overall, a third (34%) of the doctors who responded did not.

Key cause of strikes

The failure to develop a system that gives a much greater chance of career progression to doctors who have completed the first stage of their training – and the abject failure of ministers and NHS employers to take this issue seriously – is one of the major factors in the resident doctor strikes that have now begun, and will happen again, if necessary, in December).

In a half-hearted effort to head off the strike without conceding on pay, Health Secretary Wes Streeting did offer an additional 1,000 specialty training posts this year, and to increase the number of additional training posts from 1,000 to 2,000 over the next three years: but that inadequate offer has now been withdrawn.

However some significant concessions have been offered on working conditions, following on from the substantial (if belated) changes that were won during the last wave of strike action, and are now being driven through by NHS England. These concessions are supposed to tackle chronic grievances over incompetent and insensitive rota management, bungled pay packets, and the need for designated on-call parking spaces, and access to 24/7 hot meals, rest areas and lockers.

Streeting offered that if unions agreed a deal he could also:

- Pay for doctors’ royal college exam fees (backdated to April this year), and for their mandatory membership and portfolio fees (which could be worth more than £2,000 annually for surgical trainees);

- Increase the amount resident doctors can claim for relocating during training;

- Consult on prioritising UK graduates for training places, from 2027;

- Help locally employed doctors into postgraduate training;

- Increase a fixed allowance paid to resident doctors who work less than full time by 50% (to £1,500.)

All of these would potentially be attractive, but pale into insignificance in the context of up to 20,000 newly graduating doctors failing to get a place on any of the specialty training programmes … making the conditional offer of 1,000 extra places seem supremely inadequate.

The uncertainty over their future careers has now combined with the simmering resentment that resident doctors have seen the real value of their pay eroded more sharply than almost any other group of workers since the 2010s, while the apparently large settlement of the last round of strikes has still left them way behind 2008 levels of pay, with a below inflation increase set for next year.

Anger over replacement of doctors

However a further element of anger and frustration must not be forgotten, as resident doctors see a process of replacing qualified doctors up to, and including consultant level in some areas, with less-qualified Physicians’ Assistants (PAs), Anaesthesia Associates and Advanced Clinical Practitioners who are all in theory “educated to master’s level or equivalent,” although a number of courses turn out to have less than convincing pass rates of 100%.

Each of these groups of staff, with fewer years of training and experience than nursing and midwifery staff, and much less than resident doctors, begin at Band 7 (above most nurses and midwives) on the Agenda for Change pay scales (£47,810 – £54,710) giving hourly rates upwards of £5 per hour higher than medical graduates (who begin at Foundation Year One at £38,831, with FY2 at £44,439).

Since at least 2017 the argument for why PAs and ACPs were needed began with a supposed lack of junior doctors; some have also argued (despite the higher pay for more limited hours) that the use of such staff is a cash-saving measure. Neither argument is backed by evidence.

What does seem to be the case is that management have seen the extension of the role of ACPs as a way of weakening the power of doctors, and in some cases such staff are being recruited and appointed specifically to take on roles that should properly be open to doctors.

The Leng Review in July noted the lack of convincing and appropriate research on the safety and quality issues of employing PAs, and simply concluded there were:

“no convincing reasons to abolish the roles of AA or PA, although, from a workforce perspective, there is some doubt about the need for the training of further AAs.”

The review called for changing the names of PAs and AAs from ‘Associates’ to ‘Assistants’ to avoid public confusion about whether they were doctors. But on the other hand, it also recommendedthat Physician Assistants should have more scope still:

“the opportunity to become an ‘advanced’ physician assistant, which should be one Agenda for Change band higher.”

So the only thing that seems to have changed significantly is the name; the problem is unresolved.

There has been a non-stop series of revelations on social media of Trusts continuing to advertise PA/ACP posts, which clearly take over what would otherwise be resident doctors’ posts and responsibilities.

An anaesthetist noted on X/Twitter that: “The same-day emergency care (SDEC) unit in my hospital is staffed by 2 ACPs (god knows what base profession); 2 ANPs (nurses); 4 physician assistants and 1 clinical pharmacist. This means 9 doctor posts are permanently occupied by people who are allowed to work exactly as GPs (they take referrals from GPs and can reject any referral they don’t like).”

University Hospitals Dorset offered an ENT post that is clearly the proper domain of a resident doctor to an ACP equivalent. One advert makes clear that a PA is expected “to train junior residents” – i.e., a person with a Postgraduate Diploma teaching doctors who have trained for at least 5 years.

In at least two cases, adverts have sought a “Higher Level” or a “Consultant” ACP, TWO bands higher on Agenda for Change (8b) (£64-£75,000).

St George’s Hospital Trust in South London, ignoring the Leng Review recommendation, is seeking a PA to “join a growing team of Physician Associates providing care for patients admitted to Trauma and Orthopaedics,” in another job that should properly go to a resident doctor.

None of this contributes to tackling the shortages of consultants, reducing the waiting list, improving A&E services or improving the overall productivity of the NHS, which are supposed to be the government’s big concerns. To deliver any meaningful settlement with the resident doctors, Streeting has to recognise and address the underlying problems that have made them so angry … and demoralised.

The demoralisation of resident doctors is well reflected in a posting on WhatsApp, anonymised and posted online by Dr Iona Collins on X/Twitter, which ends:

“We are the ones who have kept this broken system running through goodwill, personal sacrifice, and quiet exhaustion. We are the ones who stayed while others left.

“And we’re the ones watching our own children turn away from this profession—not because they lack the intelligence or the heart, but because they saw what it did to us. If you still think pay restoration is about money, you’ve missed the point.”

Dear Reader,

If you like our content please support our campaigning journalism to protect health care for all.

Our goal is to inform people, hold our politicians to account and help to build change through evidence based ideas.

Everyone should have access to comprehensive healthcare, but our NHS needs support. You can help us to continue to counter bad policy, battle neglect of the NHS and correct dangerous mis-infomation.

Supporters of the NHS are crucial in sustaining our health service and with your help we will be able to engage more people in securing its future.

Please donate to help support our campaigning NHS research and journalism.