Like elsewhere in the economy, surging inflation is also depleting NHS budgets. Before he left the government Sajid Javid recently told the Times “the NHS doesn’t need any more money”, despite widespread calls for investment in extra staffing, instead pushing for more efficiency savings, a policy which NHS leaders are already saying is highly unrealistic.

What is enough?

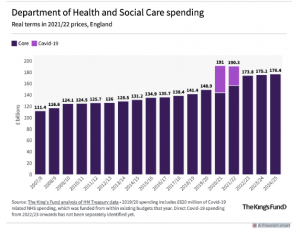

Record funding helped to meet the challenge of Covid for two years, but health spending has since fallen back to £172bn in 2022/3 – still a huge figure in comparison with other government departments, but the common view amongst economists is that it is far from enough. The huge backlog added to the damage done by an 8-year squeeze on NHS funding (2010-18) prior to the pandemic means that far greater and more sustained reparation is needed.

During Covid NHS funding reached £190bn annually, which was briefly on trend with where NHS funding would have been had it not been for the prolonged period of underinvestment (2010-18).

“the NHS is under huge pressure and while funding has increased, the extra funding is below what would be needed to make significant inroads into the long waiting lists, invest in primary and community services and put emergency care on a stable path.” – Anita Charlesworth, Director of the REAL Centre at the Health Foundation

The NHS needs around 4% annually to cover growing health costs, according to calculations by the IFS and others – although climbing inflation will push this figure up too.

Before the pandemic rise in funding averaged around 2% across the previous 8 years. Then in 2021 Spending Review the government announced that funding was set to rise by 13% between 20020/21 and 2024/25, but this has been mostly front loaded and swallowed up in the tail end of the pandemic and the resulting backlog of treatments.

Over the next two years NHS funding is set to rise by just 1.2% annually, and that is very likely to be eroded by inflation, at a time when there are key areas crying out for long-term investment.

Workforce

With a 106,000 short fall in staff, NHS leaders have named the NHS workforce crisis as their top challenge and yet there is still no fully funded workforce strategy in place. Waiting lists are rising over 6 million and health professionals are worried about declining standards of service.

An RCN survey published this year found that:

Eight in 10 (83%) said there weren’t enough nursing staff to meet all patient needs safely and effectively on their last shift.

Just a quarter (25%) of shifts had the planned number of registered nurses.

Less than one in five (18%) said they had enough time to provide the level of care they would like.

In key areas like cancer, specialists are worried that recent gains in survival rates could be lost because of delays. In a bid to speed up diagnosis the government plans to introduce 100 diagnostic hubs – mobile units in car parks and shopping centres, by 2025, but according to the Society of Radiographers lack of investment in staffing means that, under the plan the 6000 extra radiographers and other staff needed to run them will have to be transferred from elsewhere within the system.

The plan?

NHS England’s People Plan, belatedly published back in July 2020 was full of analysis and ambition, but lacked the cash for implementation. It has since been confirmed in a speech by Sajid Javid in March that although a new long-term workforce plan is on the way any new investment to raise NHS staffing levels will need to be found from within existing NHS budgets. The Treasury doors have been firmly closed, which limits the expansion of training places and the creation of the new roles that the service needs.

With every year of inaction the crisis gets worse. The REAL centre has revised their estimates because of the lack of progress on staffing, now saying that an extra 6,200 consultants (up from 4,400) and another 25,700 nurses (up from 18,300) will be needed, over and above existing NHS staff vacancies, in order to meet government targets for elective care by the end of the parliament.

Jeremy Hunt, health secretary from 2012-18 now admits that “I was too slow to boost the NHS workforce”. He can see the jeopardy the NHS is now in and from the back benches he makes a persuasive argument that it’s a “false economy not too invest in staff”, and has called for the reporting of staffing needs to be established in law.

There is some good news, as during the pandemic there was a record rise in nursing students. Figures released by UCAS, the Universities and Colleges Admissions Service, show the number of nursing applicants at English universities in 2020 rose by 25.9 per cent compared with 2019, but as the Royal College of Midwives and others have previously pointed out budgets need to rise in the NHS to employ them. The number of midwives actually fell by 331 in 2021/2022

The need for a long term funded plan covering both recruitment and retention has never been greater. The government claims that it is halfway to recruiting its target of 50,000 extra nurses, but the vacancy rate remains at around 39,000 – 10% of the workforce. The number of professionals leaving the Nursing & Midwifery Council’s is rising year-on-year, and 20% are aged 56 or older.

A steep challenge

Short termism must end as Health Foundation calculations point to the reality that the NHS workforce would need to grow by more than a third over the coming decade to tackle the backlog in treatment within the NHS and make good on current shortages of staff – that means a rise of 277,500 full-time equivalent staff by 2024/25

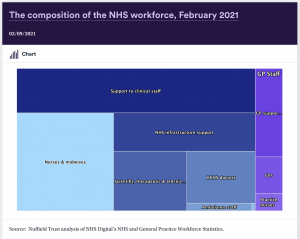

Ministers often quote rising numbers of doctors and nurses, ignoring the swathes of other crucial health professionals and NHS workers who are experiencing pressure from understaffing. Piecemeal targets tied to the Tory manifesto are too narrow a system wide strategy is what many organisations have called for.

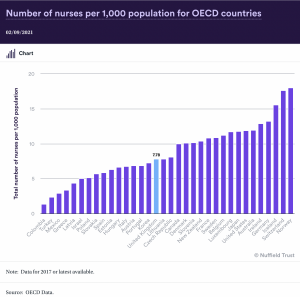

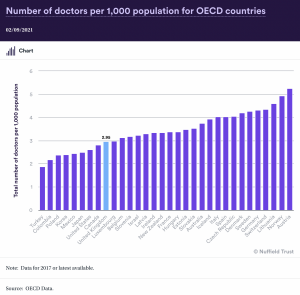

By comparison the UK has less staff per head of population than most other comparable nations

Pay deal

Retaining its staff will be all the more difficult amongst fears about a “growing exodus of exhausted staff”, Soaring inflation is cutting into the purchasing power of wages when NHS staff have already watched their pay fall in real terms over the last decade. The basic pay of nurses fell by 5% after inflation between 2011 and 2021, even though they have done better than other public sector workers.

Unison highlights too the impact on the lower paid and the unfairness within the process of pay review. “Last year’s 3% award meant a member of staff in Band 2 got an extra £580 while a member of staff in Band 8a got an extra £1,550” that widened the gap between these grades. The trade union favours a flat rate to give everyone the same cash sum, to help mitigate the cost of living amongst the lower paid.

A dispute seems inevitable though as the government are pushing for the Pay Review Body to recommend a cap of 3% across the NHS, which mean that the average NHS salary would fall by £850 in real terms.

Unite the union has confirmed that its health sector representatives will be recommending rejection of the Scottish Government’s 5 per cent NHS pay offer following a meeting in Glasgow on 16 June. The trade union will now consult its members on rejecting the offer and on a potential industrial action ballot throughout July.

Efficiency savings?

Under the banner of reducing waste the government has doubled the efficiency savings that the NHS is required to make every year from around 1% to 2.2%, or around £4.74bn in savings. A doubling of the ambition it set in its own long-term plan back in 2019. Is this realistic?

In historical terms the NHS manages an average of 1.15 savings a year, more than the wider economy

A period harsh productivity demands has been tried before. And resulted in widespread deficits, underinvestment in workforce and buildings and cuts to services, as it was accompanied by a prolonged NHS funding squeeze.

As David Maguire, a senior analyst at the Kings Fund, points out Many of the potential productivity improvement have already been tried or are already in train such as: capping spending on agency staff, improving procurement, networking pathology and diagnostic services, improving value for money in prescription spending and reducing the number of clinically ineffective treatments. so where are these savings going to come from?

Dear Reader,

If you like our content please support our campaigning journalism to protect health care for all.

Our goal is to inform people, hold our politicians to account and help to build change through evidence based ideas.

Everyone should have access to comprehensive healthcare, but our NHS needs support. You can help us to continue to counter bad policy, battle neglect of the NHS and correct dangerous mis-infomation.

Supporters of the NHS are crucial in sustaining our health service and with your help we will be able to engage more people in securing its future.

Please donate to help support our campaigning NHS research and journalism.