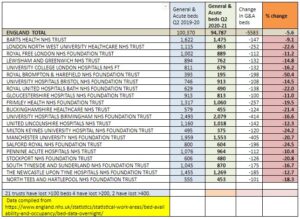

England’s acute hospitals have lost over 5,600 front line beds – an overall reduction of more than one in twenty – in the 12 months to September this year, according to the most recent NHS figures.

The distribution of these reductions is wildly unequal: some hospitals have maintained similar numbers to a year ago, or even increased front line bed provision (the largest increase being 106). By contrast 21 hospital trusts have closed more than 100 beds, 4 trusts have closed more than 200 – and University Hospitals in Birmingham and Manchester have each closed over 400.

17 further trusts have seen reductions of between 50 and 97 beds, six of them equivalent to more than 10% of beds and one (Harrogate) having lost over 26%.

The new statistics cover beds available overnight in Quarter 2 (July-September) 2020-21. They show numbers of beds that have been available this year, with some recovery from the precipitate drop in numbers in Quarter 1, resulting from NHS England’s drive to discharge tens of thousands of patients to create space and free staff to cope with the first wave of Covid.

It appears that the figures reflect efforts by trusts to separate Covid from non-Covid patients, but also their need to divert staff from more routine non-Covid services to care for patients in expanded ICU and Covid wards: with recent workforce figures still showing over 80,000 vacancies across England’s NHS, there have been only so many staff to go round.

It appears that the figures reflect efforts by trusts to separate Covid from non-Covid patients, but also their need to divert staff from more routine non-Covid services to care for patients in expanded ICU and Covid wards: with recent workforce figures still showing over 80,000 vacancies across England’s NHS, there have been only so many staff to go round.

Shortages of suitably qualified staff are also part of the reason why only a third of the private hospital beds that were block-booked by NHS England early in the pandemic were actually used to treat NHS patients.

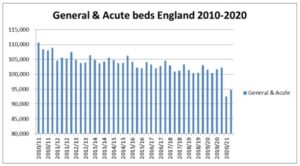

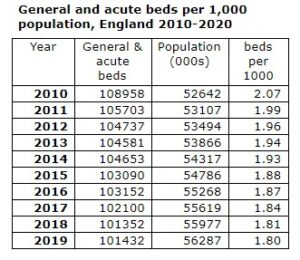

However, not all of this latest situation is down to Covid. A decade of frozen funding had reduced the NHS to a dire state before the pandemic struck, and numbers of acute and mental health beds had been falling year by year, with 13,000 acute beds and 25% of mental health beds closed since the austerity regime was imposed by the Cameron government in 2010.

Matt Hancock’s recent statement in a BBC interview that England’s NHS now has fewer than 100,000 beds – a historic low – indicates that we cannot expect all of the beds lost in the last year to reopen.

Matt Hancock’s recent statement in a BBC interview that England’s NHS now has fewer than 100,000 beds – a historic low – indicates that we cannot expect all of the beds lost in the last year to reopen.

UK provision of beds, with England as the least well provided, has for many years been well below that of comparable European and OECD countries, and this is getting worse: in 2010 England had 2.07 acute beds per 1,000 population: by last year this had fallen by over 10% to just 1.8.

This shortage of front line capacity, bringing repeated, worsening winter crises, has been the subject of repeated complaints from the Royal College of Emergency Medicine, and led to the NHS missing more and more of its key targets to reduce waiting times for emergency, urgent and elective treatment.

Although the average drop may appear unexciting at just over 5%, some of the reductions are dramatic, and some of the percentage reductions are also very substantial [see table below]: of the trusts that have lost over 100 beds only Barts has lost less than 10%, while eight have lost more than one bed in five. The largest proportional drop has been at London’s Royal Brompton and Harefield, where more than half of the beds have closed in 12 months.

The reduction of beds might have been expected to lead to a sharp increase in occupancy as NHS chiefs have attempted to create safe routes and get routine surgery back up to target levels; however only seven acute trusts show occupancy levels above 90%, and the average occupancy, reflecting social distancing and reduced levels of non-Covid activity, is just 77%, well below the 90% England average for the same quarter last year.

The longer term implications are also worrying – with the likelihood of further inroads to be made by the private sector into an under-resourced NHS. The reduction in NHS beds and reduced levels of occupancy have brought a drastic cut in NHS capacity.

But instead of investing to ensure hospitals can refit and reorganise to reopen the closed beds and recruit and train the extra staff they need, Rishi Sunak’s spending review has once more starved the NHS of resources, allocating a paltry £3 billion increase to NHS revenue spending to cover all of the increased costs, and given a one-off increase in capital – to be followed by a real terms cutback.

By contrast a lavish £10bn has been allocated to a 4-year “framework contract” with private hospitals to treat NHS waiting list patients. The danger is that NHS capacity will remain hobbled for years to come, leaving it increasingly dependent on private hospitals, with a steadily growing share of taxpayers’ money flowing out of the NHS into private pockets.

Trusts that have lost more than 100 beds since Q2 2019.

Dear Reader,

If you like our content please support our campaigning journalism to protect health care for all.

Our goal is to inform people, hold our politicians to account and help to build change through evidence based ideas.

Everyone should have access to comprehensive healthcare, but our NHS needs support. You can help us to continue to counter bad policy, battle neglect of the NHS and correct dangerous mis-infomation.

Supporters of the NHS are crucial in sustaining our health service and with your help we will be able to engage more people in securing its future.

Please donate to help support our campaigning NHS research and journalism.