Social care services are in even greater peril as figures show that councils are battling huge debts and scores of providers are selling up. The public services union, Unison has renewed the call for a national care service, releasing a strategy document, Care after Covid, to make the case for a radical shakeup.

A national care service is not a new concept, appearing in the 2010 Labour manifesto and again in 2017, although on this week’s Andrew Marr show, Labour’s Shadow Chancellor- Anneliese Dodds seemed less certain about the commitment; elsewhere a host of commentators and organisations are now backing the return to a more publicly driven structure.

This latest exploration of the idea by Unison links past and present, making the case that Covid-19 has cruelly exposed the vulnerabilities in our care system that grew from a decade of austerity and from privatisations that started in the 1980s.

Pandemic failings

Whilst NHS staff were heroes from the start, care workers struggled to get basic support. Unison reported that during the crisis that many care staff couldn’t take time off to self-isolate because of “poverty pay” in the sector. Others were denied sick pay by their employers whilst isolating, or were pressured to come into work.

Access to proper PPE has been a scandal throughout, and care workers were heavily exposed, but in a sector with 8000 businesses a coordinated response to Covid was almost impossible. The inability to collect standardised data about the number of deaths and infection rates in care homes highlighted the flaws in a system run by businesses operating individually when collaboration was key to responding to the virus.

A new mission

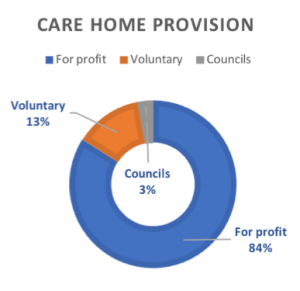

Unison’s strategy aspires to bring back inhouse care sector staff and facilities, eventually “fully integrating” with the NHS and delivering the vast majority of social care through public funding; but the union acknowledges the current reality that 97% of care is delivered by private or voluntary organisations, which means the transition to national care service will take time.

The report does not venture into how much this would cost, or set a timetable, but it does identify steps that could be taken straight away.

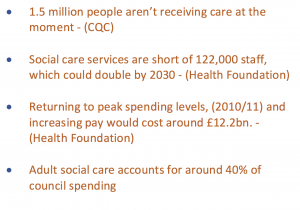

The government needs to lift overall spending on social care by 12.2bn to 2022/23 – based on estimates by the Health Foundation and this funding should be aimed at the 1.5 million people who Age UK say aren’t receiving care at the moment, but also invested in the workforce that is estimated to be short of 122,000 staff.

Funding for councils – to start to invest in bringing services back in-house, would allow for the development of training and pay that is standardised and fair, right across the sector.

Unison asserts that as a society we need to think about social care differently: “as no longer just a “cost” but an important economic sector, with investment in it helping to rebuild local economies” in the wake of Covid-19.

The New Economics Foundation, who have published their own analysis of care sector ownership agree, calling for universal care services, like the NHS : “The choice facing policymakers, both local and national, is whether to let services continue to develop in a way that is extractive, drives inequality through low-paid, insecure jobs, and puts downward pressure on the quality of care, or to intervene.”

Driven by cost

Much of the evidence confirms that the current system regularly fails to meet the needs of patients, a reality epitomised by the rigid 15-minute standard for home care visits. Care staff employed by companies work to the clock, restricted in the time that they can spend with each client, whereas community nurses working for the NHS, although working under pressure, have more freedom to adapt to the needs of the patients they visit.

However, the underfunding of councils has exacerbated the crisis, resulting in low-cost deals with providers and in unison’s view, price is steering decisions about care, and they say most councils are “failing to pay the minimum amount considered necessary to provide safe levels of care.”

“As of January 2020, there were 30 councils paying less than £500 per week for an older person in a residential care home, equivalent to just £2.97 per hour”

Changing ownership

This is a tight market and many providers are fighting for survival. Last year three-quarters of councils reported that providers in their area had closed, ceased trading or handed back publicly funded contracts.

For private equity this is an opportunity. Market conditions are shifting the ownership of home care providers as the small players sell up to firms backed by investment groups.

The largest four residential care companies provide 15% of residential beds, and just under a third (31%) of all beds are provided by the biggest 25 companies.

This hasn’t provided stability, in recent times two of the dominant players, Southern Cross in 2011 and Four Seasons in 2019 have gone into administration with councils under pressure to protect vulnerable residents.

High borrowing, low staff pay, and sharp cost controls are key features of the for-profit model, said Grace Blakeley, co-author of an IPPR report, which calls for the state to once again become a major provider of care homes by investing £7.5bn to provide 75,000 beds by 2030.

“The fact that private equity-backed firms have taken over a significant share of the UK’s care provision, fuelled by debt and driven by the prospect of rising property prices and ever-lower care costs, puts our vital social care system at ever-increasing risk,”

The IPPR report also indicates the scale of the challenge to bring back all care beds into public hands, as their plan which would still leave around two-thirds of beds being run by the independent sector. Figures produced by IPPR and Future Care Capital show that for-profit companies currently own 381,524 (83.6%) of England’s 456,545 care home beds.

However, the status quo is unsustainable. The New Economics Foundation suggests that the current government response, of producing sporadic extra funding without reform could be “propping up” a system, which increasingly channels public funds to big corporates.

Urgency as cuts approach

The current system also looks near to collapse as the rising costs shouldered by councils cannot continue to be supported. Despite an extra £3.7bn in Covid related funding from the government, the Local Government Association sees a blackhole of £7bn and research by the BBC, and CPP has discovered many councils are confronting deficits and a number are on the edge of bankruptcy.

Adult social care costs make up over 40% of council expenditure, pressing down on other budgets and several councils are already reported to be working on packages of cuts. Leeds City council is freezing recruitment and all non-essential spending and Luton, Manchester, Wiltshire, and Liverpool have also raised concern about their finances.

Despite recent funding, the trend has been to cut spending in real terms. The IFS calculates that austerity measures nationally have driven down spending on adult social care by 7% per person in the past decade.

Low pay and poor standards

Unsurprisingly low pay and poor working conditions are prevalent. A quarter of care staff are employed on zero-hours contracts. There is a big turnover, a third of care staff leave their roles each year and there is a major shortfall of 120,000 staff, which could double by 2030.

Not all parts of the UK currently have professional registration for care workers, and changing that is Unison say, one way of ensuring a more consistent approach to standards and boosting the prestige of care work.

Inadequate across the UK

All four home nations view their social care systems as inadequate and are looking towards reform, but there are already significant differences, most notably in Northern Ireland where health and social care have been fully integrated.

All four make use of means-testing to control access, but as a Nuffield Trust article points out the funding offer in England is the least generous: “Scotland has free personal care, Wales operates a weekly cap on non-residential care costs, and Northern Ireland provides domiciliary care services free of charge.”

How to get there?

Few are suggesting a rapid transition to public ownership, perhaps due to the immediate cost and the near total dominance of the private sector, but the New Economics Foundation suggests ways to start the process: by giving local authorities new powers to buyout providers that are failing or consistently providing poor quality care and, crucially to provide new sources of finance. The government should, NEF say, promote cooperatives and provide employees with first refusal to buy out care providers as businesses come up for sale.

The NEF also suggested bolstering the Care Act 2014 to place a duty on local authorities to “promote diverse forms of democratic ownership across domiciliary and residential social care provision”, as a counter to the market. Of course, the market intended to provide choice, but its failure should prompt us to change tack, to involve the public and organisations in commissioning to make it “collaborative rather than competitive”.

Promises of actions

Boris Johnson promised to “fix social care once and for all” in England. After the last election he backed this up with a pledge to provide a plan for solving social care within a year and to introduce changes by 2025. We are still waiting for his plan, but there are more reasons than ever to leave behind an era of failed market based-solutions.

Dear Reader,

If you like our content please support our campaigning journalism to protect health care for all.

Our goal is to inform people, hold our politicians to account and help to build change through evidence based ideas.

Everyone should have access to comprehensive healthcare, but our NHS needs support. You can help us to continue to counter bad policy, battle neglect of the NHS and correct dangerous mis-infomation.

Supporters of the NHS are crucial in sustaining our health service and with your help we will be able to engage more people in securing its future.

Please donate to help support our campaigning NHS research and journalism.