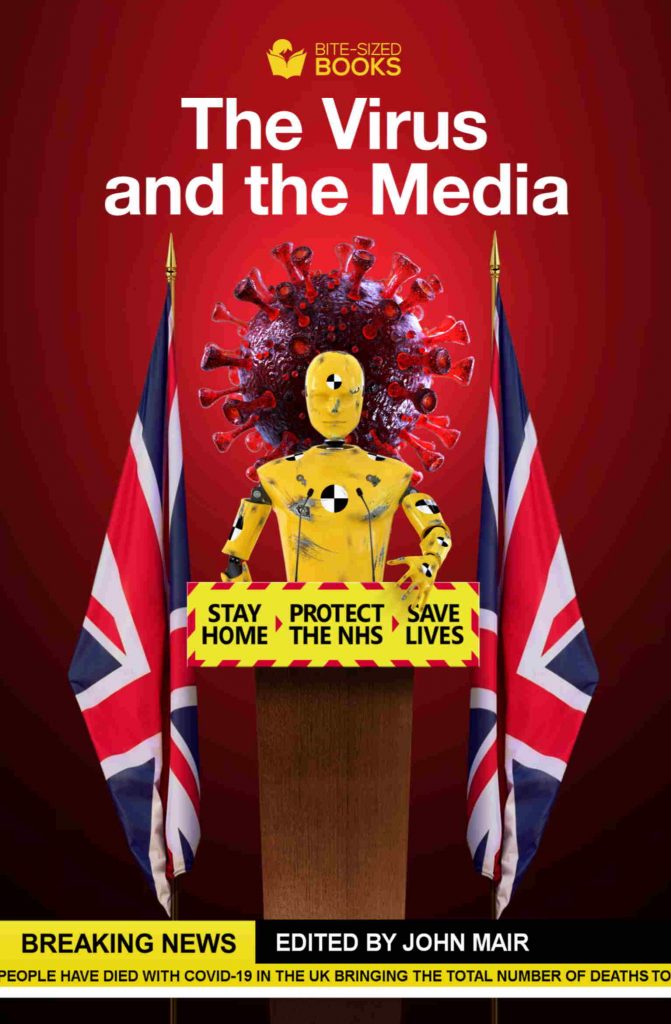

This is a chapter by JOHN LISTER that has just been published in The Virus and the Media, a new book in which a distinguished cast of journalists, commentators and academics have each written articles on their understanding of how well journalism – online, broadcast and print – has presented what has happened to the public.

It all appeared to be going splendidly. The news media latched on to the scale of achievement of converting the massive ExCel conference and exhibition centre into a huge “NHS Nightingale” field hospital with up to 4,000 beds in just nine days. The irony that Florence Nightingale’s fame was as a nurse struggling to save the casualties of Britain’s disastrously bungled war in Crimea was overlooked.

With ministers apparently emulating North Korea’s public relations style rather South Korea’s prompt and effective public health measures to contain the virus, this seemed a brilliant way to distract journalists away from any scrutiny of embarrassing questions.

These include the dire shortage of hospital beds driven by ten years of frozen NHS budgets, Britain’s poor level of provision of intensive care beds and equipment compared with similar countries in Europe, the desperate shortage of nursing and medical staff, the lethal lack of personal protective equipment (PPE) and incompetence distributing it, and ministers’ failure to act on previous warnings of gaps in readiness to cope with a pandemic.

Some media reports even compared the rapid completion of the reconfiguration of the London Nightingale with the massive Chinese effort in Wuhan, which involved clearing land and building several vast prefabricated hospitals from scratch in just ten days.

On Friday April 3 when Prince Charles opened the new London Nightingale field hospital by video link all the news headlines were about the great effort that had been made. Print and broadcast media regaled us with awkward photographs of the grand occasion, with England’s Health Secretary Matt Hancock standing proudly as the Great Helmsman at the forefront of a line-up of staff, spluttering into his handkerchief after self-isolation with suspected Covid-19.

Who would have guessed that just a month later, with British death levels the highest in Europe, the hospital would have closed, with much less pomp and circumstance? It had actually used just 42 of its potential 4,000 beds, and barely touched much of the new equipment that had been supplied. At the peak of Covid admissions over Easter weekend, the London Nightingale only had 19 patients.

Limiting factors

The whole stunt swiftly unravelled. Despite fanfares for the discharge of the Nightingale’s first cured patient, the more astute journalists from left and right have continued to point out that two limiting factors have doomed this and the other nine Nightingales from the outset. The first and potentially the most crucial is the chronic lack of staff: even in the final few days before it was closed (AKA “on standby,” or “mothballed” in readiness for a second surge) NHS England bosses had to tour London’s hospital trusts demanding CEOs take staff from their work and dispatch them to join the limited team at the ExCel centre in Newham. Where sufficient volunteers could not be found, reluctant trust bosses were required to select staff and dispatch them.

Most in demand were the very intensive care (ICU) nurses – who were most needed in their own hospitals. Even the less sophisticated anaesthetic ventilators – the main type installed in the Nightingale – required experienced staff to make proper use of them.

Attracting staff became harder when some early volunteers came back to tell of the frustration of treating a small handful of patients in a large soulless building with an excess of doctors and nursing staff, knowing the pressures on their colleagues back at their own trusts. At the end 200 staff were on duty on May 4 to look after just 12 Nightingale patients.

Journalists also began to highlight the second limiting factor, the confusion over the role of the new hospitals. Although it was billed as offering expanded ICU capacity, admission criteria for the London Nightingale appear to exclude patients requiring full ventilator treatment (any patient scoring above five on the clinical frailty scale). Any patient with significant complications or serious intensive care needs such as renal replacement therapy, or filtering blood in place of the kidneys, was excluded.

Hospitals left with sickest

London hospitals, which had expanded ICU provision in existing hospitals (often by converting operating theatres into makeshift ICUs) were left to treat the sickest patients. They somehow coped with the demand, but hospital trusts in and outside London became even more resistant to NHS England pressures to refer patients to the London Nightingale.

A detailed Independent report was the first to explore the problem in depth: the hospital had too few patients to justify its existence… but too few staff to take any more. It also lacked any surgical facilities, so was not able to offer any additional capacity to treat the growing waiting list of patients waiting for elective operations. It was neither fish nor fowl.

As David Rosser, chief executive of University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust said of the Birmingham unit: “Is it as good as a bed in a hospital? No, not by a long stretch. It remains fundamentally a warehouse with beds in it.”

Local news media also began to criticise the nine additional Nightingale-style hospitals created at huge expense elsewhere in Britain, none of which have had more than a handful of patients.

Birmingham’s Nightingale in the National Exhibition Centre (NEC); Manchester’s Nightingale in the main hall of the former Manchester Central Conference Centre; the Harrogate Nightingale in the Convention Centre (opened by Captain Tom Moore) and Bristol’s Nightingale hospital at the University of the West of England between them had up to 4,000 beds. Almost none of them were used.

The North East Nightingale in Washington’s ‘Centre of Excellence for Sustainable Advanced Manufacturing’ barely even opened, and a Nightingale hospital in a former Homebase store in Exeter didn’t open at all.

Devolved administrations followed the Westminster line, with the 2,000 bed Dragon’s Heart Hospital at Cardiff’s massive Principality Stadium becoming the second biggest white elephant after the London Nightingale.

Only in Belfast was a hospital building used – converting City Hospital’s tower block into a 230-bed unit. And only the NHS Louisa Jordan at the Scottish Events Campus (SEC) in Glasgow (named after a Scottish nursing heroine who died in the first world war) has been publicly costed, offering up to 1,000 beds at a cost of £43m, even though Scottish ministers were relatively confident it would never be needed. It wasn’t.

More questions are now being asked, as the PR triumph backfires. While the London and Birmingham hospital sites have been made available rent free, it’s not clear how much has been spent on the Nightingales. But while the makeshift hospitals have done little or nothing for patients, the new hospitals have improved the health of balance sheets for private contractors including KPMG, Mott McDonald, Archus, and Interserve who were given contracts without competitive tendering under pandemic procurement rules.

It’s not just the building work that has offered profitable contracts: support services were also contracted out. ISS were brought in to clean and dispose of waste at the London Nightingale and G4S was given the contract for security at all ten Nightingale hospitals.

Private hospitals

Fewer questions have so far been asked about the wisdom of NHS England paying an estimated £300 per bed per day to use 8-10,000 beds in private hospitals, most of them small buildings lacking any ICU capacity and geared only to uncomplicated elective surgery. But the Daily Mail reports large numbers of these beds are also standing empty, no doubt because of their limited usefulness and underlying shortages of qualified staff.

Indeed there is growing media concern over the 40% of acute hospital beds (37,000) left silent and empty after 33,000 patients were hurriedly discharged and almost all NHS elective treatment halted to clear space for potential Covid-19 patients.

However ONS figures have now revealed how many thousands of these people have instead been dying without NHS care, especially after untested patients were sent home or dumped (under emergency legislation) into residential care and nursing homes.

The real cost of the Nightingales won’t be measured in cash terms but also in lives shortened or lost among non-Covid patients as staff and resources were misdirected into useless vanity projects.

While front line staff have been left frustrated and idle in Nightingale hospitals, fear of Covid-19 infection has apparently deterred huge numbers of patients from seeking emergency treatment. Thousands of stroke and heart patients have stayed away from A&E departments, while NHS England as recently as the end of April was insisting on the “paramount” need to free up beds usually occupied by stroke patients … to care for those suffering from coronavirus.

Some reports have highlighted frightening projections of thousands of deaths as millions of outpatient appointments have been cancelled and many hospitals cancelled all cancer surgery. The Royal College of Surgeons are warning that it could take five years to clear the “mountain” of a waiting list that was rising even before the Covid crisis.

So while it all started well for ministers, it has ended badly for patients and staff – slumping from Nightingale to Nightmare in just one month.

Too many inquisitive journalists have meant government efforts to spin their way out of a pandemic have ended in tears.

The Virus and The Media, How Journalism Covered the Pandemic is available now as a download from Amazon, or from Bite Sized Books.

Dear Reader,

If you like our content please support our campaigning journalism to protect health care for all.

Our goal is to inform people, hold our politicians to account and help to build change through evidence based ideas.

Everyone should have access to comprehensive healthcare, but our NHS needs support. You can help us to continue to counter bad policy, battle neglect of the NHS and correct dangerous mis-infomation.

Supporters of the NHS are crucial in sustaining our health service and with your help we will be able to engage more people in securing its future.

Please donate to help support our campaigning NHS research and journalism.