At the end of March Health Secretary Matt Hancock finally axed the long drawn-out and shambolic project to reconfigure hospital services in North West London. He told MPs that the plan which was once held up as a model for others to follow is no longer supported by the Department of Health and Social Care, by NHS Improvement, or NHS England.

But it’s not only ministers who are now distancing themselves from this failed project. Since Hancock’s statement many key players, including senior figures from NHS England’s shadowy London Regional office, some of whom have since reinvented themselves as management consultants, will have been praying the embarrassing details will be swiftly forgotten or buried. There is a lot for them to keep under wraps.

While the headline cost of the whole scheme rocketed from £190m to over £1 billion, project costs for the hugely expensive ‘Shaping a Healthier Future’ (SaHF) scheme frittered away more than the cost of a substantial-sized new hospital, but delivered nothing but a stack of flawed and incomplete documents. These included one of the largest-ever preliminary documents in the NHS (2,700 largely unread pages in 7 giant volumes of the “Decision Making Business Case” published online in 2013, a download totalling 86 megabytes).

By the end of 2017, when SaHF stopped publishing information on the costs of management consultants, local experts had already totted up official figures revealing a staggering total of £72,285,181 squandered in five years on management consultants.

However consultancy fees were only a minor component of spending on the SaHF project over the whole 7 years of the project: advisors to the Commission led by Michael Mansfield QC which investigated the plans in 2015 used actual figures from NHS reports, coupled with informed estimates, to estimate that the total costs by 2017/18 would be a massive £235m.

SaHF project leaders claimed they “did not recognise” the figures – but have never published any alternative figures to show how much has been spent. In June 2016 they revealed that a small army of 130 people, including 75 “interim executives” were employed on the project, and that more than a hundred of these would still be in post by March 2017.

Despite these lavish resources, and multiple contracts for management consultants to complete a final business case, the project which began in 2012 had not done so 7 years later. So poor was the plan that it had its application for capital funding rejected twice by NHS England and NHS Improvement citing the very problem highlighted by campaigners – a lack of detail on how care was going to be reprovided.

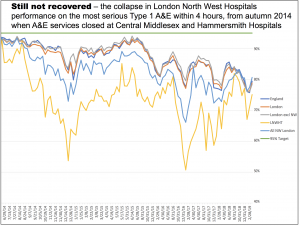

Nor did the services of consultants including McKinsey, Ernst & Young, PwC and Deloitte prevent the adoption of deeply flawed proposals. The closure of A&E services at Central Middlesex and Hammersmith hospitals in the autumn of 2014, triggered a disastrous – but entirely predictable – plunge in A&E performance standards.

It later emerged that (as critics of the plan had warned) the project leaders had made significant errors in calculating the numbers of beds required. Only now, almost five years later and after extra beds have been opened has performance in London North West Hospitals been restored to the level it was at before the closures.

The SaHF project never won any public acceptance in the boroughs it most affected: in fact it was instrumental in the Conservatives losing control of one of their flagship London boroughs, when a Labour campaign won Hammersmith & Fulham council pledged to fight for Charing Cross and Ealing Hospitals. The determination of this council to halt plans to downgrade and close local services played a major role in delaying the process and allowing reason to prevail.

Even local trust bosses began to distance themselves from planned cuts in bed numbers.

Indeed few people who were not paid to do so ever shared SaHF’s ambition to close acute services and demolish the main buildings at Charing Cross and Ealing Hospitals, and sell off most of their sites to developers, building minimal new “hospital” facilities on small residual plots.

Few people believed the heroic assumption that as yet unbuilt “community” and out of hospital services would result in drastic reductions of patients requiring emergency hospital care (99,000 fewer by 2025) and allow a net reduction of 364 beds in “outer NW London” and further cuts adding up to 500 beds overall. However the damage done especially to Ealing Hospital by the SaHF plan lingers on. Its services were fragmented and downgraded with the loss of maternity and paediatric services, and the looming threat of impending closure of more services and restricted scope for training doctors made recruitment and retention of medical and nursing staff more difficult. As yet no plans have been published to reverse or repair any of this.

The problems also extend to Charing Cross and St Mary’s hospitals, part of the Imperial Healthcare Trust, which as The Lowdown reported in February has the largest backlog maintenance bill in the country, adding up to a massive £649m. Scrapping the plans to asset strip Charing Cross to raise capital to rebuild the crumbling St Mary’s, which in some cases is actually falling down, leaves the urgent question of how urgent repairs and upgrades are to be paid for while the austerity regime prevails in the NHS.

Now the plan has been scrapped and the arguments largely discredited, campaigners are also pressing for the Public Accounts Committee or National Audit Office to mount a rigorous external inquiry into how so much time and money was wasted by so many – to deter any NHS managers who looked to NW London as a model from following down the same dead end.

Some of those responsible who have since scuttled off to become chief executives or management consultants rolling out similar nonsense elsewhere need to be called to account.

As Karl Marx said, those who cannot learn from the errors of the past are doomed to repeat them, and any attempt to use the SaHF fiasco as a learning exercise requires a rigorous critique of why it went so wrong and wasted so much money at a time of great financial hardship for the NHS.

Dear Reader,

If you like our content please support our campaigning journalism to protect health care for all.

Our goal is to inform people, hold our politicians to account and help to build change through evidence based ideas.

Everyone should have access to comprehensive healthcare, but our NHS needs support. You can help us to continue to counter bad policy, battle neglect of the NHS and correct dangerous mis-infomation.

Supporters of the NHS are crucial in sustaining our health service and with your help we will be able to engage more people in securing its future.

Please donate to help support our campaigning NHS research and journalism.