This week the health and select committee within Parliament confirmed what everyone working in the NHS already knows – it has a major staffing crisis, The Tory leadership candidates are not offering any new policy ideas, but a new NHS plan is desperately needed, covering all the major factors that affect the capacity of our NHS.

KEY FACTORS

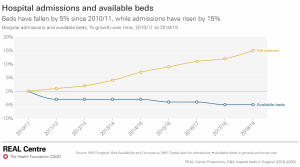

- Pressure on hospital beds – hospital activity is lower than before the pandemic, whilst the number of Covid in-patients has risen sharply recently. The trend in the total number of hospital beds has been downward and historically the UK has worked with a smaller stock of hospital beds than most other countries, leaving dangerously low spare capacity.

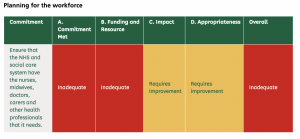

- An inadequate workforce strategy – a decade without the proper NHS workforce planning has been exposed by the current staffing crisis. There are 106,000 unfilled posts across the NHS, so retaining the current staff must be a priority. NHS staff are already demoralised – another real-terms pay will not help. Delays in immigration visas for staff is also not helping. In the short term, efforts to fund extra staffing were made more difficult after the insistence from government that the cost must come from existing budgets. Judged by a panel of experts to be “inadequate”, the current strategy should be rewritten to include a major step change in training and recruitment across the NHS. This is crucial to meet projections of high future demand. So far a funded plan has not been produced.

- Underinvestment – Despite raised funding in the spending review settlement analysis viewed it as not enough to expand activity. The upsurge in inflation will devalue budgets further, leaving no room to settle crucial pay negotiations. A further rise has so far been refused and instead ministers have imposed demands for what seem to be unachievable efficiency savings, a controversial tactic which has previously led to service cuts.

- Problems with buildings and equipment – Government will spend 3.7% more annually by 2023/4 on capital, but these rises come after ten years of underfunding led to a £9bn backlog in hospital repairs, so the new funding is a welcome start, but more is needed upfront to deal with £4.9bn of urgent repairs.

- Growing reliance on private sector – the published NHS recovery plan places heavy emphasis on support from private hospitals, but they have a relatively small number of beds and share many surgeons with the NHS, giving limited scope for expanding capacity this way. Longterm, outsourcing lowers standards according to a recent study, a view supported by 200 0phthalmologists who wrote jointly concerned about affects on eye patients.

- Pressure on social care – After years of neglect by all governments, the recent changes to limit the individual care costs do nothing to attack the major supply-side issues – chiefly, the reliance on a shrinking commercial home care sector. The care sector has its own staffing crisis too, short of a 100,000 care workers. An already overstretched NHS has become the prop for the lack of care services.

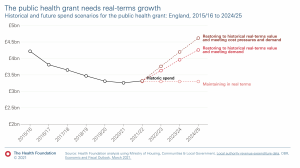

- The neglect of prevention – public health services have endured real terms cuts of 24% per capita in the funding paid to local authorities to prevent obesity and smoking, and to pay for children’s services (2015-21). Current funding still falls well short of the projected need.

Policy makers have consistently failed to address these key factors. Without adequate action on them, bringing the NHS out of crisis so that it can provide timely, high-quality care to the whole community will be impossible to achieve.

Other factors?

There are clearly other factors that affect capacity – style of management, career development, support for staff, action on issues like bullying and discrimination have all been recognised in the NHS People Plan.

Technological advances will continue to make a huge difference in healthcare but despite the claims of policy makers they offer no immediate silver bullet to the problems of understaffing, building repairs and pressure on GPs and require proper planning and investment to make sure of the benefit.

Like any large organisation the NHS can be inefficient. Expenditure on temporary staff, management consultants and PPE contracts has been excessive and wasteful. And yet many years of underfunding has already driven managers to strip back waste and reshape activity. Digital projects, can improve data handling, diagnosis and disease management, but since ambitious targets were set little progress has so far been made.

MORE DETAIL ON THE KEY FACTORS

Pressure on hospital beds

During the pandemic NHS hospitals closed beds to help control the spread of infection. And by the end of 2021 there were 3,385 fewer beds occupied than before the pandemic (2018-19), and planned hospital activity levels have dropped too, down by 12%.

Covid continues to have an impact with a sharp rise in the number of covid patients to around 9000 in hospital, up from 3,800 in just one month (June)

There has also been a long-term decline in NHS bed numbers that pre-dates the pandemic, the UK works with a smaller bed capacity than other countries – the average number of beds per 1,000 people in OECD EU nations is 4.6, Germany has 7.9, whereas the UK has just 2.4.

The number of maternity beds decreased from 7,906 to 7,668 (a 3% decrease) between 2010/11 and 2021/22, a trend which has contributed to the trend of maternity units being forced to close to new patients during busy periods.

As in other countries the average length of time that in-patients spend in hospital has been reducing. More surgery is performed on a day case basis, although the number of day beds has risen by only 200 since 2010/11, whereas the total number of overnight beds has fallen by 12,000.

Due to the lower bed stock in the UK bed occupancy rates are often higher than the safe minimum (85%), and certainly higher than in other comparable countries, leaving too little spare capacity in the system to cope with seasonal fluctuations. Combined with the pressures on social care, and lack of investment in staffing this has been the recipe for regular periods where patient care is compromised because the NHS is overstretched.

Lack of a funded workforce strategy

NHS leaders name the lack of staff as their top challenge. This key function – of planning adequate staffing levels has been failing for a number of years. Despite the publication of the NHS People Plan – the funding to bring about a planned step change in staffing across the NHS has not been made. In fact, before he resigned Sajid Javid clarified in a speech in May that no new money would be available for extra staffing.

The result is that NHS staff are under far greater pressure, trying to care for the rising numbers of patients, but increasingly staff are finding working conditions unacceptable, higher numbers are retiring early or leaving the NHS because of the pressure.

With every year of inaction the crisis gets worse. The REAL centre has revised their estimates because of the lack of progress on staffing, now saying that an extra 6,200 consultants (up from 4,400) and another 25,700 nurses (up from 18,300) will be needed, over and above existing NHS staff vacancies, in order to meet government targets for elective care by the end of the parliament.

Progress?

Progress?

Overall NHS number of staff has risen by 2.2%, but of the current nursing posts 50,000 are unfilled, along with 12,000 medical vacancies. As the REAL centre figures indicate the size of the NHS workforce will need to rise significantly over the next few years.

Manifestos pledges:

6,00o more GPs?

In its manifesto the Conservatives promised 6000 more GPs – there are now 1,608 fewer fully qualified full-time equivalent GPs today than there were in 2015, Each practice has on average 2,222 more patients than they did then. GPs have on average 37 patients contacts a day when the safe level is 25, increasing the risk of fatigue, poorer care and burnout.

50,000 new nurses?

Despite ministerial claims to be on track, recent the target will be missed by 10,000 according to the latest predictions. In 2022 the nursing sector still has a vacancy rate equivalent to ten per cent of the workforce. Aside from the problems with pay and moral, one in five nursing registrants is aged 56 or older – and therefore likely to retire within the next few years.

District nursing numbers have fallen by 46% since 2009, and are down over the last 5 years too, despite government promises on staffing, whilst caseloads are climbing.

One in 10 of psychology, psychiatry and therapist jobs are vacant in the NHS.

340,000 cancer patients face late diagnosis due to NHS staff shortages.

The number of midwives has fallen by 300 in the last year. the Royal College of midwives warned of a midwife exodus due to overwork and the fear that they cannot deliver safe services.

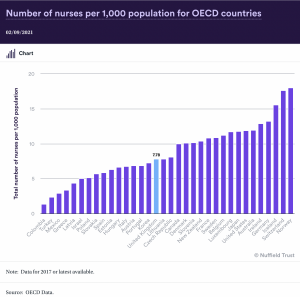

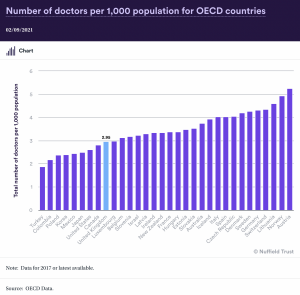

It will take until 2046 before the NHS has the number of practicing doctors per 1000 people required to match today’s OECD EU nations’ average. We are therefore 25 years behind according to the BMA.

A study by Stanford University School of Medicine found that doctors who reported at least one major symptom of burnout were more than twice as likely to have reported a major medical error within the previous three months.

Doctors responding to the NHS staff survey, 57% said they would go to work even when feeling unwell, and 77% report experiencing unrealistic time pressures elevating the risk to staff and patients.

A panel of academic experts have recently produced this summary of the current workforce strategy, based on a full report for a committee of MPs investigating the issue, judging it to be “inadequate”.

The scale of the challenge has not yet been grasped by policy makers. Not only have they to make up for years of underinvestment, the sharp rise in health need from the growing numbers of older people and those living with chronic illness means a huge new training and recruitment drive must start now.

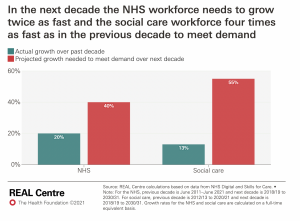

Analysts at the REAL centre calculated that by 2030/31, up to an extra 488,000 health care staff would be needed to meet demand pressures and recover from the pandemic – a 40% increase in the workforce and double the growth seen in the last decade. They also found that 6oo,000 extra social care staff would be needed – 55% more, and 4 times greater than the increases of the last decade.

Buildings and equipment – “40 new hospitals”?

After analysis the government’s claims to be building 48 new hospitals seem completely over blown as the true figure is nearer 6 – three projects to rebuild non-urgent care hospitals and only three are new hospitals. According to research by the Nuffield Trust, a further 22 are renovation projects on existing buildings and 12 are new wings within existing hospitals.

Laurie Rachet-Jacquet, an economic analyst at the Health Foundation, told the BBC: “They are not all ‘hospitals’ as most people would recognise them.” She suggested that cost building 40 new hospitals would be far higher. “Around £3.7bn has been committed to the Hospital Building Programme. But according to NHS Providers, a mid-sized hospital costs around £500m. Forty completely new mid-sized hospitals would therefore require in the region of £20bn – not £3.7bn.”

These headlines distract from the more damaging neglect of capital budgets leading to a the massive £9 billion backlog for maintenance – which according to the latest ERIC figures rose almost 40% in 2019-20, and is now almost as large as the whole of the current DHSC capital budget, and the cost of running the entire NHS estate (£9.7bn)

The government has made some progress announcing annual increases of 3.7% by the end of 2024/25 in real terms, however more immediate funding is needed as £4.9bn to the deal with the urgent work, assessed to be a ‘significant’ or ‘high’ risk, threatening patient safety.

Alongside its increased spending commitments announced after the Spending Review in October 2021, a list of projects have been also been talked up by ministers, with impressive yet opaque price tags. Below health researcher and writer Dr John lister gives his over view and raises doubts about the scale of funding and whether they can achieve their stated goals…

“£4.2 billion by 2025 “to make progress on building 40 new hospitals by 2030 … and to upgrade more than 70 hospitals”. £4.2bn is nowhere near enough. In fact all of the prioritised new hospital projects are at a standstill, with new limits on spending causing chaos. The invitation for bids for an additional eight new hospital projects to bring the total to 48 has resulted in an additional barrage of hugely expensive, unaffordable schemes. And a string of 1970s-built hospitals across the country are increasingly unsafe as concrete planks crumble, requiring hugely expensive stop-gap measures, and threatening to collapse on patients and staff.

£2.3bn by 2025 to “transform diagnostic services with at least 100 community diagnostic centres …”. However the first such community diagnostics centre, recently opened in Somerset, turns out to be yet another project reliant on the private sector. It is being run by Rutherford Diagnostics Limited, in partnership with Somerset NHS Foundation Trust. Peter Lewis, chief executive of Somerset NHS Foundation Trust, told the local press: “We entered into our partnership with Rutherford Diagnostics Limited in June 2020 because, despite our investment in MRI and CT scanners, and our continued use of mobile scanners, we were concerned that our trust would not keep pace with demand for diagnostic tests in the future.” For similar reasons it’s likely most if not all of the new centres will also expand the use of private companies.

£2.1bn by 2025 for “innovative use of digital technology” – another door opened for expensive whizz-kiddery and unproven apps and systems, with control divided between NHS Digital, NHSX and NHS England.

£1.5bn by 2025 for “new surgical hubs, increased bed capacity and equipment.” This sounds a lot but is equivalent just over £3mn per year per acute trust: and new beds and equipment beg the question of where the staff can be found to allow them to operate properly.

£450m by 2025 for projects in England’s 54 mental health trusts, allegedly to replace dormitories with single en-suite rooms, and invest in new facilities linked to A&E and “to enhance patient safety” – again a pathetically inadequate amount to pay the rebuilding and other costs involved. “

Funding – What is enough?

Record funding helped to meet the challenge of Covid for two years, but levels have since fallen back to £172m in 2022/3 – still a huge figure in comparison with other government departments, but the common view amongst economists is that it is far from enough. The huge backlog added to the damage done by an 8-year squeeze on NHS funding (2010-18) prior to the pandemic means far greater and more sustained reparation is needed.

The NHS needs around 4% annually to cover growing health costs, according to calculations by the IFS and others – although climbing inflation will push this figure up too.

Before the pandemic rise in funding averaged around 2% across the previous 8 years. Over the next two years NHS funding is set to rise by just 1.2% annually, and that is very likely to be eroded by inflation, at a time when there are key areas crying out for long-term investment.

A key plank in the effort to retain staff is the provision of cost of living increase for all NHS staff, but current budgets only provide for a rise of 3% and so minsters will have to produce more funding to make any reasonable settlement affordable for NHS employers.

Privatisation

Large contracts have been signed with private hospitals to-help with the waiting lists. It is is important to have this fallback for those patients that can’t get timely treatment but there are major flaws in the governments current plans, which has so far proved poor value.

There is limited scope for private hospitals to expand NHS capacity, they can only provide a fraction of their 8000 beds (which under 10% of the NHS bed capacity). Most surgeons working in private hospitals also work in the NHS and so there is a limit to the extra work they can do before they are reducing the time they spend on NHS patients.

Private hospitals are not evenly distributed across the country, but concentrated in London, the south east and more prosperous populations. Deprived areas will be left out of this aspect of the recovery plan.

Privatisation of the NHS has been found to correspond to a decline in care quality and “significantly” increased deaths from treatable causes, according to a study from researchers at the University of Oxford.

The study – Outsourcing health-care services to the private sector and treatable mortality rates in England, 2013–20: an observational study of NHS privatisation – published in The Lancet Public Health analysed data from Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) in England and the researchers concluded that:

In the letter, signed by nearly 200 ophthalmologists and sent to NHS England and the Royal College of Ophthalmologists and shared with The Independent, they warn of “the accelerating shift towards independent sector provision of cataract surgery” which is already having a “destabilising impact” on safe ophthalmology provision.

They predict that the wide scale use of private providers will “drain money away from patient care into private pockets as well as poaching staff trained in the NHS.” adding that “urgent action” is needed to prevent further work being given to the private sector.

CHPI director David Rowland expressed similar concerns to the newspaper: “There is a big risk that unless government provides adequate funding for the NHS, more and more people will be forced to pay privately, which in turn will undermine middle-class support for a tax-funded NHS.” He predicted the possibility of ending up with a two-tier system, where the NHS is a residual service for those without the means to pay.

Social Care

Almost 170,000 hours a week of homecare could not be delivered in the first three months of 2022 due to a shortage of care workers, according to the latest Waiting for Care and Support report from the Association of Directors of Adult Social Services (ADASS), and the number of people waiting for assessments, reviews or care to begin is now at over half a million.

The first three months of the year saw a 671% increase in unmet hours compared to spring 2021, according to the survey, which also found a 16% increase in the number of hours of homecare that have been delivered compared to spring 2021.

The number of people waiting for assessments, reviews, and/or care support to begin as of February 2022 was 506,131, a significant increase from the 294,353 people reported as waiting in September 2021.

As well as the high level of unmet need for many in the community, the problems in home care have a knock-on effect – NHS hospitals struggle to discharge patients back home, which in turn reduces beds available for patients from A&E and for elective care, which contributes to ambulance waits, cancelled clinics and cancelled operations, and makes it more difficult for hospital trusts to reduce waiting lists and respond to emergencies. Furthermore, prolonged stays in hospital can increase the risk of infection for the patient and a deterioration in physical and mental health.

ADASS warns that

“Existing challenges of rising requests for support, increasing complexity of care required, fragile care markets, and underpaid, undervalued and overstretched workforce, risks being compounded by the current cost of living crisis.

Public health

Dear Reader,

If you like our content please support our campaigning journalism to protect health care for all.

Our goal is to inform people, hold our politicians to account and help to build change through evidence based ideas.

Everyone should have access to comprehensive healthcare, but our NHS needs support. You can help us to continue to counter bad policy, battle neglect of the NHS and correct dangerous mis-infomation.

Supporters of the NHS are crucial in sustaining our health service and with your help we will be able to engage more people in securing its future.

Please donate to help support our campaigning NHS research and journalism.