For the first time more than 50% of NHS patients referred for hip and knee replacement are being treated in the private sector. This care is funded by the NHS, but spotlights a growing reliance on the private sector and the failure to build sustainable NHS capacity.

Meanwhile in the care home sector we see the price of such dependence where eight out of ten are run for profit, but many are now closing, pushed under by Covid shocks and the previous funding squeeze.

It is adding to the pressure on NHS hospitals, as patients are stranded unable to be discharged from hospital beds because of a lack of care home places.

The fate of the health sector – still mostly publicly run, and the largely private care sector are locked together, both in peril, for lack of public funding and action around securing enough health and care workers.

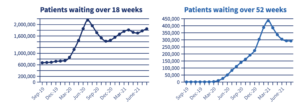

For the public, long waits and the impression of a worsening NHS are now leading to increasing numbers of better-off patients opting to pay for their own private care. Public confidence in the NHS is taking a knock.

Ministers blame the reverberations of the pandemic, they are silent on the origins of the problem and talk up the future. Back in the real world, there is a growing sense of jeopardy and acknowledgement that both sectors still lack the workable plan they need to respond to the crisis that consumes them. Ministers have a further chance to act in the Comprehensive Spending Review due at the end of October.

A stack of think tank reports chime on the previous failures of policy. Too often investment has been too slow and when it arrives insufficient. The latest increase for the NHS will help across the next two years according to the IFS, but not for the medium term and is certainly no solution for social care.

The government is still not getting the message even though the latest shocking workforce estimates suggest that the health and social care sector need to recruit over a million extra staff before the end of the decade, an intimidating task given the government failure to recruit 6000 extra GPs, in fact numbers have barely increased.

In England the NHS has a workforce plan, which true to form has been hampered by delays in funding, but these plans do not stretch to anything like the step change in capacity building that is suggested by the Health Foundation estimate. Advances in areas like digital health – a ministerial favourite, can help, but won’t be enough.

The alternative path that the government seems more likely to follow is to continue to underfund, or at best pursue a just-in-time funding policy, leading to insufficient staffing growth. Concurrently they are pursuing the old habit of encouraging further reliance on the private sector to bolster NHS capacity.

In mental health – where 44% of the child and adolescent mental health budget is spent with private providers, in diagnostics and in parts of community health, the private sector has become central to the delivery of mainstream clinical services. These companies have growing control, and often despite some damning criticism of their performance.

The adversity of Covid has fast-tracked some outsourcing and supplied the justification too. The network of NHS labs was bypassed in favour of partnerships led by the private sector, and the pandemic had barely receded before ministers announced that this policy was to be further expanded.

Incidentally, it was confirmed in a new analysis this week that private hospitals who took an estimated £400 million a month in payments to provide access to 8000 beds at the start of the pandemic had infact very few NHS patients to occupy them. And now that long NHS waiting lists are driving up demand for private care, companies appear less keen to help out with NHS patients.

This shines a light on the reality that the NHS and the private sector don’t share the same core interests. It is unlikely that private hospitals will use the £10bn opportunity the government has created for them to perform surgery on NHS patients, as they can earn more from their private patients. For-profit companies also tend not to seek NHS contracts to provide care to the poorest communities, despite their greater need.

So failure to invest in raising NHS capacity, in NHS staff and buildings, will inevitably mean letting the private sector have greater control in our NHS, and will challenge the delivery of comprehensive care to all of us, will leave huge inequalities in the service in place, and do little to improve the prevention of future sickness too.

Dear Reader,

If you like our content please support our campaigning journalism to protect health care for all.

Our goal is to inform people, hold our politicians to account and help to build change through evidence based ideas.

Everyone should have access to comprehensive healthcare, but our NHS needs support. You can help us to continue to counter bad policy, battle neglect of the NHS and correct dangerous mis-infomation.

Supporters of the NHS are crucial in sustaining our health service and with your help we will be able to engage more people in securing its future.

Please donate to help support our campaigning NHS research and journalism.