While many campaigners’ eyes have been focused on the football, or the ‘dead cat’ of the Health and Care Bill, professional bodies have been trying to focus attention on the crisis of capacity has been racing out of control in England’s hospitals.

The normally docile Royal College of Physicians chose the NHS 73rd birthday to publicise scary new survey findings showing more than a quarter of senior consultant physicians expect to retire within 3 years, many within 18 months – and pleading with government to pump extra resources into training new staff, giving the NHS “the best birthday present it could ask for – more capacity.”

The RCP argues for three things tight-fisted Chancellor Rishi Sunak is unlikely to agree — a doubling of medical school places, alongside increased spending on social care, and action to address health inequalities.

Meanwhile the Royal College of Emergency Medicine has focused on the extraordinarily high numbers of attendances at the more specialised Type 1 A&E units, and the even higher proportion of patients with conditions so serious they need immediate admission to a bed.

1,436,613 patients attended Type 1 Emergency Departments in June 2021, the highest ever figure since records began. More than a quarter of these 400,826 (27%) were admitted, and the total of all emergency admissions (535,000) was also the highest ever in June, when there has normally been less pressure on the NHS.

But with capacity still significantly reduced as a result of the Covid pandemic, the larger numbers led to more people facing delays, with only 73.2% treated or discharged within 4 hours – by far the lowest June percentage on record, with 1,289 patients delayed by 12-hours or more – almost double the figure of the previous month.

Dr Katherine Henderson, President of the Royal College of Emergency Medicine, said: “We have a serious problem in urgent and emergency care. We are deeply concerned. We are facing record breaking figures in the high summer. We can only begin to imagine what this winter may bring.

“We ask that there is a transparent discussion about how the whole of the health service deals with the current levels of demand. Emergency care does not happen in a vacuum but is often the canary of the system.”

The Independent has also flagged up long waits in A&E, with patients waiting up to 15 hours to be seen in Plymouth’s Derriford Hospital, and up to eight hours at Leeds Teaching Hospitals Trust on Wednesday, where operations for some cancer patients were cancelled due to an increase in coronavirus patients.

The impact is also being felt by ambulance staff, where The Independent reports having seen data showing thousands of patients are being kept on hold for at least two minutes before 999 calls are answered, while new figures show record numbers of trips to A&E last month, and four ambulance trusts have issued “black alerts”, with ambulances queuing outside hospitals to admit patients.

The pressure is not restricted to acute hospital services: NHS Providers’ CEO Chris Hopson points out the increase in people in contact with mental health services – up 9% to 1.42m in April compared with 2020, with a 14% increase in front line care contacts, and a massive 54% increase since last year in out of area placements of mental health patients for whom there is no local bed.

The pressure has meant that even though trusts managed to reduce waits over 18 weeks by 80,000 and waits of more than a year by 50,000, the waiting list as a whole grew again – to 5.3 million.

Meanwhile the Royal College of Emergency Medicine has returned to a familiar campaign – demanding a restoration of the numbers of front line beds. An explanatory paper notes the continued decline in bed numbers since 2010, that was worsened by measures to address the Covid pandemic, and reminds us that the coming winter and future peaks of demand will require the lost bed to be brought back into use.

The RCEM calculates that over several year the average number of admissions per bed has been 11.7, and from this estimates that depending upon the scale of the winter pressures the NHS needs to reopen between 5,000 and 16,000 beds.

Of course the extra beds would also raise the need for extra staff – which the RCEM and other professional bodies have been demanding for several years.

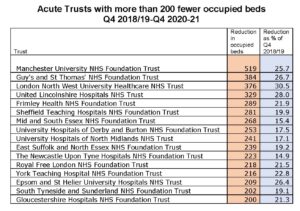

Meanwhile Lowdown has been looking more closely at the uneven level of bed reductions across hospital trusts in England, comparing the most recent figures for occupied beds (Quarter 4 2020-21) with the equivalent pre-Covid figures (Q4 2018-19).

We calculate that the England average reduction of occupied beds in that time across all trusts is 14.1% – but 79 trusts have lost a higher percentage, and the percentage loss of occupied beds varies sharply. Among the acute trusts the reduction varies between just 1.2% (Warrington and Halton Teaching Hospitals and Portsmouth Hospitals) and 30.5% (London North West University Healthcare). Nineteen more acute trusts have lost one in five (20%) or more of their occupied beds.

On numbers of occupied beds lost, the England total is 14,562 since the equivalent period in 2019, but at trust level Manchester University FT tops the list having lost 591, followed by Guy’s & St Thomas’ FT (now merged with the Royal Brompton) with 384, London North West (376) and United Lincolnshire Hospitals (329), while eleven more acute trusts have lost the use of between 200 and 289 beds since 2019 (see table).

Last year NHS England began a debate on the costs of reorganising and refurbishing hospital buildings to restore the lost capacity – but this debate has ground to a halt for lack of capital even for basic maintenance, where the backlog bill is now in excess of £9 billion.

So while the NHS is unable to use all its own beds to treat waiting list, emergency and Covid patients the private sector is delightedly stepping in to provide capacity to treat NHS funded elective patients under a massive £10bn 4-year “framework agreement.”

It should be clear to all that without a major government U-turn, to implement a programme of capital investment to reopen NHS capacity, at the end of this 4-year period the NHS will have become institutionally dependent upon private sector beds to maintain its elective caseload – and the biggest-ever privatisation of clinical services will have been carried through without any systematic protest.

This also makes a nonsense of any talk of “integrated care”: billions will be flowing out of meagre NHS budgets into the coffers of private hospital corporations, leaving front line services starved of resources, while scarce NHS nursing and medical staff will have to be split up with teams having to work away from the main hospital sites in small private hospitals – making them unavailable to assist teams coping with emergencies and complex operations.

The under-funding of the core NHS services is emerging as the most cynical and effective means to drive increased privatisation – well before the Health and Care Bill is debated or makes any impact.

Dear Reader,

If you like our content please support our campaigning journalism to protect health care for all.

Our goal is to inform people, hold our politicians to account and help to build change through evidence based ideas.

Everyone should have access to comprehensive healthcare, but our NHS needs support. You can help us to continue to counter bad policy, battle neglect of the NHS and correct dangerous mis-infomation.

Supporters of the NHS are crucial in sustaining our health service and with your help we will be able to engage more people in securing its future.

Please donate to help support our campaigning NHS research and journalism.